The name Armin Kõomägi needs no introduction in Estonia. In 2006, he burst onto the literary scene when his very first published text won the coveted short story award with playful ease. Since then, each of his books has been eagerly awaited. Published in 2015, Lui Vutoon received Estonia’s most important novel prize and has since acquired cult status, even among young readers who are otherwise not particularly interested in literature. Anyone wishing to borrow it from the library must queue. The same applies to the novel Taevas (Heaven), published last year, which has become a bestseller.

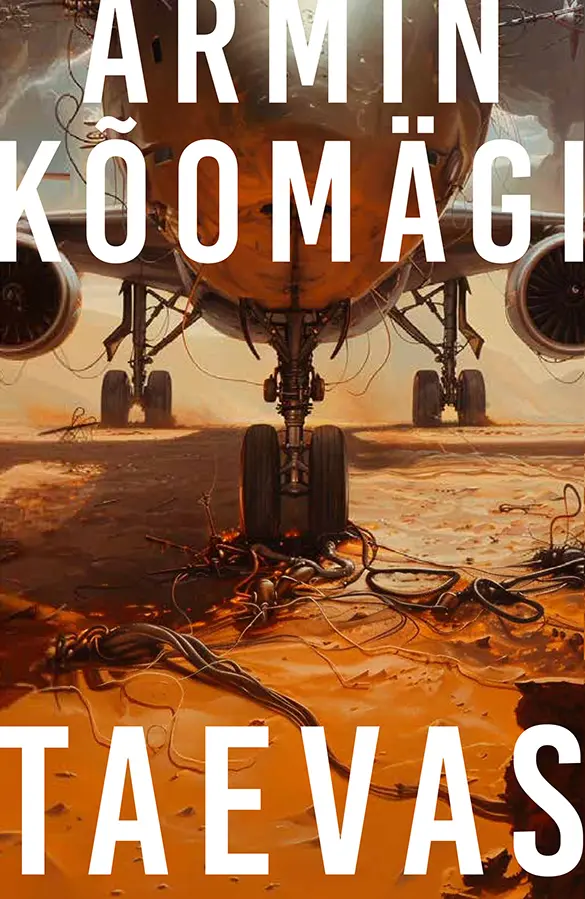

Heaven was deliberately written to be a hit, with strong potential to appeal to an English-speaking audience. The story is simple and universally understandable: the inhabitants of Earth have turned life on the planet into hell, leaving no place for humanity. Where there is no war, there are nuclear tests, burning forests, or airports occupied by animals displaced from their habitats. Of course, Kõomägi exaggerates to show us the world we are heading towards – but his fantasy is no longer so far removed from reality.

The protagonist, who has lost his memory, has no choice but to redeem his ticket for the next flight immediately after landing, as the sky is the only safe place where he will not be instantly handcuffed or killed in yet another natural disaster.

Humanity, having destroyed the planet, has nothing better to do in the cabin of an aeroplane than to sizzle the last remaining prawns and kangaroos, pour alcohol, and stage drug-and-sex orgies, while the captain who once made announcements to the passengers is no longer on board. The human soul, left in orbit, may turn to the gods it has known so far – but they no longer take calls. There is nothing but emptiness and chaos, with no hope left for anything.

Despite this hopeless setting, the novel is written in such a way that it is both enjoyable and even fun to read: one eye weeps while the other laughs. Kõomägi’s irony and sarcasm concerning humankind are cutting, but not without a healthy sense of humour and an appreciation of the grotesque. The story would be a perfect fit for the cinema – and hopefully it will find its way there soon.