A View of Eternity

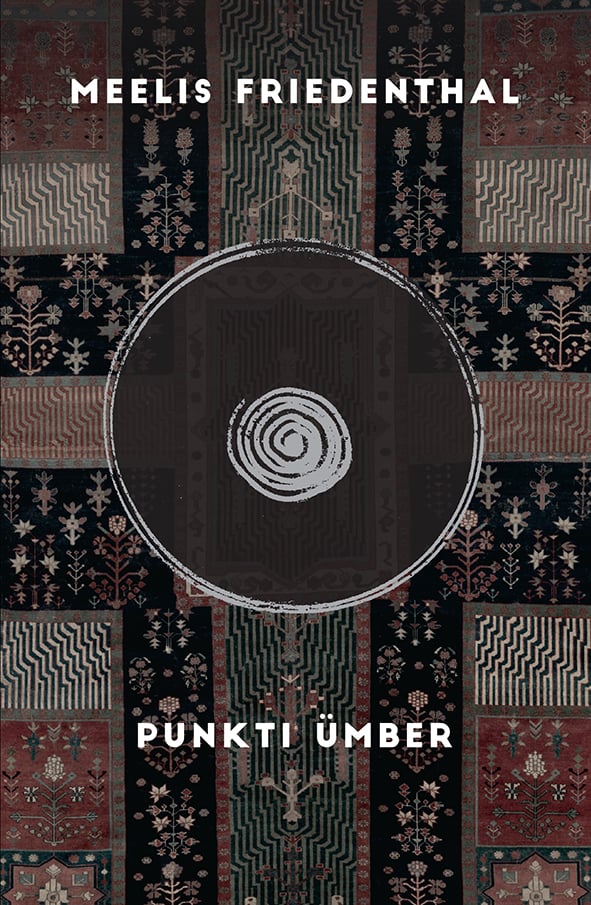

Around a Point (2023) is the fourth novel by author, academic, historian, and associate professor of intellectual history Meelis Friedenthal. Friedenthal’s approach to literature ranges from science fiction – Golden Age (2005) to philosophically tempered historical fiction – The Willow King (2012, English translation 2017, a notable and award-winning novel) and The Language of Angels (2016). He has also published a collection of short stories titled Everyone Will Be Brought To Life (2020). In my estimation, novels are where Friedenthal shines the most. His academic background grants a wealth of knowledge and sources, which he applies to paint convincing and authentic-feeling (versimilitude) within period-accurate fictional spaces. The balancing act of borrowings, quotations, references, and intertexts may be challenging, but the uniformity of the result is a convincing polyphony, a symphony of life.

Around a Point, while heavily fictionalised, is inspired by the real life of Friedrich Jürgenson (1903-1987). As Friedrich lived through a whirlwind of great events, ideological disputes, wars, and tragedies, so does Verdi, his fictional counterpart. Both Jürgensons pass through a life filled with suffering and death, and find themselves in liminal spaces – internally (between life and death) and in time and space. The novel considers, among many other themes, the question of belonging. What it means to be a member of a culture, what it means to relocate to a “foreign” culture, and the challenges such circumstances entail. Verdi passes through several different cultural spheres, where languages, peoples, religions, and histories collide. His liminality starts at birth, from having different national identities, a chasm that only deepens through his later status as a refugee. The novel frames the refugee identity as though it is a type of departed person, a ghost torn from life, who must perhaps accept their own death in order to begin living again. Verdi hopes to reach Estonia, a place with familial roots, but even this small country is a periphery, an intermediate area – the ancient historical-mythological Hyperborea – a border country. And borders are largely arbitrary, drawn throughout history by maniacs with too much power; so, where exactly is home? Perhaps it is not a place at all, but an act that requires choice and effort.

Yet, the novel is not only about Verdi. Instead, it revolves around that void-like point in the title. A light-absorbing dot from whose gravitational pull nothing can escape. It is about nothingness and non-existence; about the end of matter, reality, and being; about the underworld and the garden of paradise, whose terrifying presence has been perceived – and will continue to be perceived – by countless people. František Kupka, Kazimir Malevich, Edvard Munch, Wassily Kandinsky, and many others – several of whom are mentioned in the book. In the case of trauma and tragedy – the existentially terrifying perception of the void – a question has revolved around the possibility of depiction. How can one even comprehend such events and then describe or draw them? Without trivialising, without embellishment.

But the finale of the novel carries a life-affirming message, because Friedenthal writes life-affirming literature – the novel incorporates a demonstration of alternative paths in the life of Verdi Jürgenson and asks, in this sequence of possibilities, each of which leads to differing outcomes, which choices are the “correct” choices? And it gives an answer: to choose according to your dreams, in the name of life itself. As people, we should make the effort. Likewise, even though mimetic, “realistic” art is incapable of capturing the full reality, just as the most authentic biography isn’t enough. We should all try to act in the name of life and try to leave a mark on everyone and everything that has existed. The reality of the world revolves around a point that causes terror, the fear of death, of non-existence, of loss, of nothingness, but through acts of creation, of representation and preservation, we can give everything the right to life. There is always more truth and reality outside art – words, paintings, music, etc., – but we should still attempt to capture the facets and shards of a reality that cannot be fully comprehended and represented. It is a doomed endeavour to try to capture a singular reality anyway. We are the caretakers of meaning.

This review was first published online in Spring 2025 and later appeared in the Autumn 2025 print issue.