Étude

On the second of May, Ilona and I travelled to Taevaskoda. We had little money, and that was all we could afford. I had passed through Taevaskoda as a child and no longer remembered on which side of the railway the river lay. Ilona had never been to South Estonia. She mentioned something about the Ahja River and its reed beds. We followed some anglers and ended up at a shop. We bought a bottle of Asunik white vodka, half a loaf of bread, and two hundred grams of tea sausage – supplementing the pastries and Kelluke lemonade we had brought from the city.

The shopkeeper told us the river was on the other side of the railway, so we headed in the direction he indicated. As we walked through the small town, Ilona clung to me affectionately, hanging around my neck and half-trying to kiss me. I kissed her a couple of times in the woods before we turned toward the river. We descended into the valley and found ourselves at Small Taevaskoda.[1]

Then something strange happened to Ilona, at least from my perspective. She removed her headscarf, threw off her nylon coat, and started skipping ahead of me. I picked up her scarf and coat, stuffed them into my bag, and trailed behind her, looking for a good spot to sit and eat.

We encountered a group of schoolchildren bustling around tiny creatures that had washed up on the sandy riverbank. I wanted to take a closer look at the little fish, but Ilona didn’t let me, pulling me away by the hand. She said I would disturb the children.

Half-walking, half-running, we reached Large Taevaskoda.

I had not even set my bag on the grass when Ilona said: ‘Oh, I’d love to be alone!’

I had expected this, though not expressed quite like that.

‘Go,’ I told her.

And Ilona ran into the woods.

‘Don’t come back!’ I shouted after her. She disappeared silently into the trees.

I spread out her coat and unpacked our supplies onto the grass. I drank a sip of lemonade, followed by a big swig of vodka. Then I bit into the sausage and repeated the cycle two or three times. I started to feel relaxed and lay back on the grass like an old tarboosh basking in the sun.

Ilona was gone for a long time. I even thought about throwing a tantrum and leaving, abandoning her coat and a rouble. But I decided to wait and see what would happen. She returned laughing loudly. She must have had something funny to tell me.

I stood up and, without saying a word, knocked her down. Then I knelt and slapped her face with my open hand. Ilona didn’t say a word. It all happened so unexpectedly. She only groaned in anger and tried to get up.

I grew tired of the struggle, and she managed to rise and run a little distance away. I rushed after her and knocked her down again, this time violently. She cursed and struggled to her feet, then lunged at me. She had long arms, and one of her punches landed on my stomach. My vision went dark for a moment, and I doubled over. At that moment, another punch struck my face.

Ilona was speechless with rage; she just growled. I let out a pathetic cry and collapsed onto her. I pressed my hand to her throat. She bit my hand, and taking advantage of my shock, she started running.

‘I’m leaving for good! Keep the coat and the chunk of ham as a souvenir!’

I chased her, pinning her body against the ground, holding both her hands with my left. With my right, I stuffed her mouth with reed grass and dried moss. Ilona sputtered but didn’t cry.

I left her standing. She stayed put, head lowered. After a while, I cleaned the dirt off her back and smoothed her hair.

‘I love you,’ I told her, and gently laid her on my coat. ‘Why don’t you cry?’ I asked.

‘There are no tears. I haven’t had any for a long time. Give me something to eat.’

We ate the sausage and ham and drank the vodka. After resting for fifteen minutes, we headed to the railway station. The train arrived shortly after, and we returned to Tartu.

[1] The two Taevaskoda sandstone outcrops (Small and Large) lie on the banks of the Ahja River in Southern Estonia. The site is rich in legends, and ‘Taevaskoda’ translates as the Chamber of Heaven.

Translated by Kristjan Haljak and Slade Carter

Blind and Deaf Plates

The story was first published in the Autumn 2025 print issue.

Eleven dinner plates and a few platters were already on the table, but the food had still not been brought. The women said that today they were making a stew that needed to be cooked on two stoves, and that the second stove, on which the potatoes were boiling, had not been drawing since the morning.

Sitting alone at a table laid with empty plates is not as awkward as two people sitting together. We were at our places, my nephew and I, and we discussed the weather and politics, but neither of us dared talk about the food. Yet time dragged on, and bread, salt and mustard, knives and forks were brought, but still no food.

I handed my nephew an empty platter.

‘Perhaps some meat?’

‘I don’t feel like meat …’

I raised another empty platter towards him.

‘Fried fish?’

‘I don’t want fish either …’

‘Let’s start with potatoes then …’

Having run out of platters, I handed him one of the plates. My nephew did not respond.

‘I can serve you, just say what you’d like.’

‘Perhaps some potatoes.’

I used a fork and picked out some air potatoes and rolled three on to my nephew’s plate. He thanked me.

‘Go on, the potatoes are already quite cold … they’re starting to turn blue.’

‘I don’t care for plain potatoes … It feels like something’s missing.’

‘Rye bread, white bread … sauce? Of course, sauce!’

‘Sauce, please.’

‘Exactly, plenty of sauce, white and mild.’

The hostesses came from the kitchen to watch us. Neither they nor the strong kitchen smells disturbed us. My knife and fork clattered on the plate, as if I were eating hungrily … jealously, gorging myself. But my nephew was waiting for something.

I marvelled at everything I had set before him for his prospective dinner. Why wasn’t he eating? Was he being fussy?

‘I am not being fussy, I just have no appetite,’ he pre-empted me.

‘No appetite? Appetite, appetite at an empty table, when air potatoes are on the menu!’

My nephew threw his fork down on to the table with deliberation; his entire half-hearted attempt at gameplay had dissipated.

‘One of us … one of us has to eat! Who? If you don’t eat, then it must be me! One out of eleven, and I will eat, and when I am full I will get up from the table right away, and I will start shouting. You, however, don’t sit there scratching your chin or looking hungrily towards the kitchen! There is nothing there. You no longer know how to live, how to eat if there is nothing in the kitchen.’

And at last, my nephew began to talk.

‘You know, I don’t know how to eat these phantom … feasts. Of course, I understand that you’re not playing with me. I also know that tailors sewed garments of air for naked emperors, but I know nothing about eating like this … And why would you, of all people, teach me to eat like this?’

‘Enough! When your stomach is empty, then eating is all about you, the eater – what else is there to say about teaching? Can you teach an adult to eat?’

I paused a little then continued.

‘I am glad that I see everything differently, that I am not hungry to see everything in this world …’

‘What does seeing things differently mean?’ my nephew fired back. ‘Do you think I’m blind? That you are playing with a blind man? And …’

‘And if you were blind, I would still force you to eat, just like this. Someone has to be on my side. A selfless game has not and never will blind the sighted – quite the contrary.’

‘But if I were a deaf-mute then … would that be a capital offence?’

‘Ah, so deaf-mutes can’t be served a fantasy instead of potatoes? You can, sometimes you must – it is advisable … A deaf-mute and a stew have something in common …’

‘Where have you experienced anything as atrocious as that?’

‘In a prison camp … And remember, in the camp such games were played only on blind people.’

‘The beasts!’

‘Maybe, but we no longer know who … we only know that it was not the blind, definitely not them, because when a sighted person starved to death after such a table game, the blind were the ones who survived since they did not take part in the game. Some of them didn’t even lose weight. They said that playing the empty table game – starving compared to blindness, compared to eternal darkness – was a trivial and passing thing, overcome by imagination alone, and that the day would come again when one can eat, but the blind will never see.’

‘Why were you so unfair to the blind?’

‘You couldn’t hit the blind; you would never raise your hand to them. They could either be killed or nourished by the game, only the bad ones, of course, even in the camp.’

I had gone too far, as if I had swallowed a big empty mouthful.

‘Let’s leave the deaf-mutes in peace today … Dinner will be a little late, and the wishes and misfortunes of a couple of early diners are of no significance. But if you think I was playing a bad joke on you, then …’

I did not finish. I quickly grabbed an empty plate and smashed it against the tiled stove. My nephew sat looking on as though it were normal behaviour.

‘Don’t break the crockery … don’t break it for no reason.’

‘I shall break it. All eleven plates will be smashed into pieces against the stove … I hate plates, silent and empty. I’ll get into trouble or will be denied food for the next few days, but right now I will smash the dishes. Completely sober, I will smash these empty dishes and expectant plates.’

‘Do it then!’

And I hurled all eleven plates (incidentally, my nephew was eleven years younger than I) against the stove. The hostesses shouted, cursed and regarded both of us strangely. My nephew grinned stoically. His smirk didn’t feel at all out of place, albeit highly sinister. The smirk apologized out loud for something; it also felt as if he were doing so on my behalf.

‘Why are you throwing plates at the stove?’

‘I don’t know …’

‘Anyway, new plates are being brought … We won’t have to wait any longer for the stew, and there will be no escape from eating.’

Once again he smirked.

‘You are to blame for my smashing the plates!’ I yelled at my nephew.

‘Perhaps indirectly, but still it was you who smashed the plates.’

‘You are clearly the more guilty.’

‘Clearly a witness, you mean to say.’

‘Don’t argue. You are guilty because you did not take the empty plates and empty table game seriously. Only for a brief moment did I feel that you could no longer tell the difference between a full and an empty plate, that it might be possible for you to eat a meal of thin air, anywhere, at any time … You must have been critical at that point, too … a shame.’

‘I was!’

‘If you were, why weren’t you angry with me? What a joke – and yet not a single serious complaint from you.’

‘You could not insult me, offend me; you’d have to try a lot harder to manage that.’

‘And we will eat again as always … All right. The food is coming, but remember, nephew, this isn’t over yet. The score is still not settled.’

‘Possibly, but I no longer believe that you are capable of settling scores.’

‘I am, and so are you!’

‘It remains unfinished.’

‘What remains unfinished?’

‘Dinner.’

I suppose it was, because while I was eating I had the feeling that I had already paid for dinner long ago in some bureaucrat’s office.

Translated by Slade Carter

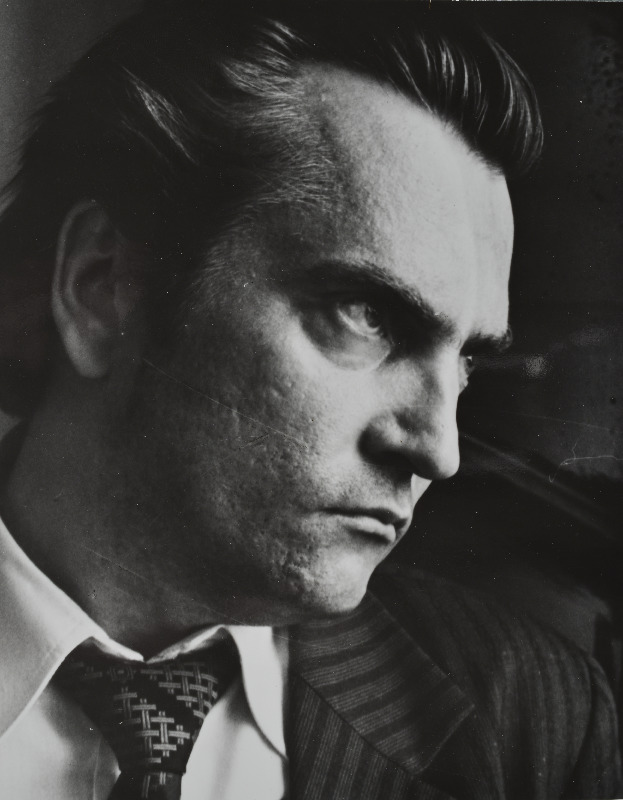

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Vaino Vahing (1940–2008) was an Estonian prose writer, playwright and psychiatrist, renowned for his psychologically intense and autobiographical work. A central figure of the Sixties generation, he was closely associated with writer and director Mati Unt and deeply influenced by the darkly lyrical prose of Jaan Oks. Vahing’s Nõva Street salon in Tartu became a hub of avant-garde culture, where intellectuals gathered for philosophical roleplay and theatrical games. He explored psychoanalysis in both life and literature, often refusing to separate the two. His notable works include Machiavelli kirjad tütrele (Machiavelli’s Letters to His Daughter, 1990), the short story ‘Etüüd’ (‘Étude’, 1968), and the novel Endspiel: Laskumine orgu (Endspiel. Descent into the Valley, 1988) (with Madis Kõiv). He was also a pioneering force in Estonian independent theatre publishing through the Thespis almanac.

‘Etüüd’ (‘Étude’) was first published in the November 1968 issue of the magazine Looming. The story portrays Spiel as a psychological game enacted in private situations, where mental and physical violence were, at least ostensibly, placed in the service of metaphysical aspirations. While considered transgressive in its time, the piece’s strange and striking allure continues to captivate even half a century later.