FRIDAY: PARTY at 8 p.m.!

Nina was the one who wrote on the notice board: ‘FRIDAY: PARTY at 8 p.m.! Everyone makes their favourite dish.’ Everyone and their, so inclusive. S., who had just arrived on a writers’ residency, was intrigued to find out the ratio of males to females in the house. She stared at the list of names on the board and the list stared back with a certain hint of promise, because finding someone to sleep with was easily a possibility in larger houses like this. Line. Lise. Kristine. Each with a surname that was either Danish or Norwegian.

She recalled a crappy bang during a lovely Danish residency. It’d been with a tattooed Danish sci-fi writer three years her junior. He’d been high and dry for a year; S., on the other hand, had recently gone through a flurry of bland partners in an attempt to overcome a broken heart. The whole fling with the sci-fi writer was just bland, dry, and desperate, but they carried on for several nights and afterward, S. remarked: ‘Thank you, I needed that.’ And the sci-fi writer replied: ‘Thank you, it was delicious.’

She wouldn’t mind finding something similar now. Something detached, enthusiastic, and the end of which neither party would lament. Alas, the list read Line, Lise, Mathilda, Kristine, Jaana, Nina, Irena, and Daniela. S.’s eyes paused momentarily on a Dagbjört, but what followed revealed she was somebody’s dóttir. Malkhaz and Pablo. Now we’re getting somewhere. Hlosukwazi? Hlosukwazi, as it soon turned out, was an art historian only staying for two days. Hlosukwazi was also a voluptuous young woman who wore a flat cap and vivid green fingernail polish.

So, a favorite dish. That was a lot to ask for. It sounded almost like a prime literary work in such a setting. Jesus, just imagine: all those tipsy writers harping on the nitty-gritties of how to cook duck with rosemary or an oven-baked beef tenderloin in cherry sauce. S.’s favorite dishes were made by restaurant chefs.

‘It can be anything, really,’ Nina clarified on that sunny Friday afternoon. ‘I’m just going to stick to tuna salad. With olives.’

S. then recalled a handsome young illustrator-boy on that same Danish residency. He’d made glass noodles with shrimp and chicken one night, which involved very little hassle and turned out looking very fancy. S. found the recipe online and composed a shopping list.

4 packages of glass noodles

4 limes

shrimp (preferably tiger shrimp)

chicken

lobster tails

garlic

Thai fish sauce

olive oil

ginger

celery

When she entered the kitchen, carrying all the necessary ingredients (only the tiger shrimp, which had made the illustrator-boy’s meal so appealing, were missing, but oh well), Nina and Jaana were already working on their contributions. Nina smiled as she mixed tuna with olives and hard-boiled eggs. She was a Slovenian author and extremely congenial. The tuna contained mercury in some quantity or another. Jaana was preparing a chanterelle mushroom sauce. She was a Finnish poet and a translator from Russian who wrote poetry on women’s issues; a sweet and motherly person.

‘I picked them myself. They are my poems for today,’ she purred.

Dagbjört showed up wearing white Old-Roman-style sandals and long crocheted knee-high stockings. She labeled her footwear ‘perverse’. Dagbjört intended to whip up a big pan-sized omelet – the thick, fluffy kind with vegetables.

Pablo was a plump and merry Honduran-born performance poet

Pablo. Pablo was a plump and merry Honduran-born performance poet who’d grown up on the West Coast of the US. He drew illustrations on a projected digital tablet while reading his poems on stage. Pablo headed straight to the box labeled ‘FOR EVERYBODY’, which contained previous residents’ leftover foodstuffs. Such receptacles usually contain ample supplies of spaghetti, couscous, bulgur, granola, and flour. Pablo indeed decided to make couscous with diced cutlet and sausage, taken from his own reserves. Boiled sausage and a semi-processed slab of meat.

Bingo, S. mused. So far, her dish seemed to be the sexiest of the lot. She elegantly opened a bottle of Pinot Grigio, offered everyone else a glass, and got down to work.

The dish was as salty as sea water and revolting.

Seafood and chicken – both looked delicious after initial preparation. You only need to soak the glass noodles in water for a moment. Then came the Thai fish sauce. Garlic. The recipe yielded a huge batch, simply gigantic. S. utilized one of the largest bowls she could find in the communal kitchen. She tasted it again after it was complete, but now, something was off. The dish was as salty as sea water and revolting.

Candles were lit on the table.

Niceness, unadulterated niceness filled the air

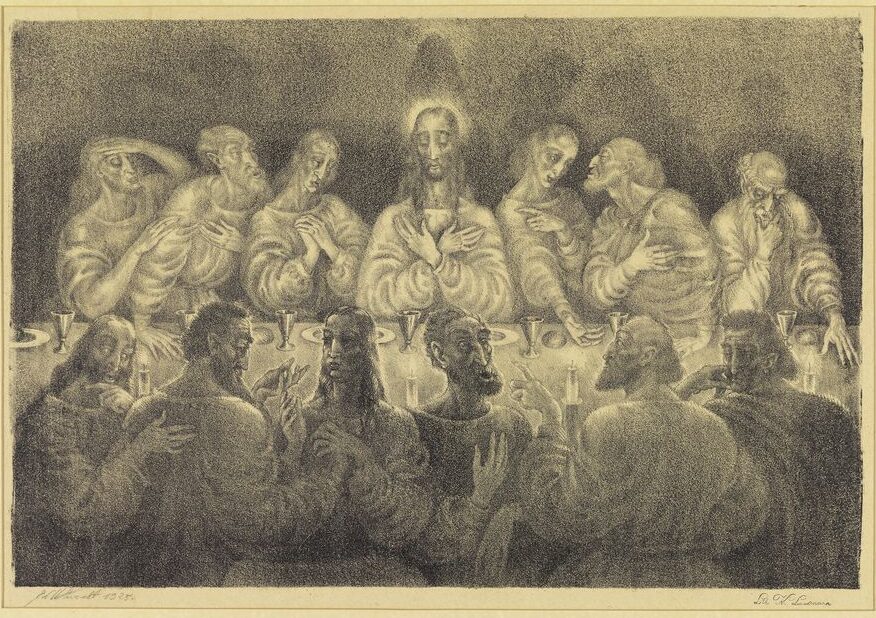

Niceness, unadulterated niceness filled the air of the dining nook: oh, what a table, what aromas, wow, just look at your makeup.

Valentina, a chubby Belarusian writer in a white lace blouse, sat down next to S. She spoke only Belarusian and Russian, and was thus limited to three or four conversation partners in the setting. Valentina was a wunderkind who published her first book at the age of 12 and was presently working on a ‘punk play’ by night. She always woke up at two in the afternoon, went straight to the kitchen, and boiled up spaghetti. The woman ate them plain, adding no sauce or seasoning. S. reckoned the Belarusian would be a grateful consumer of her glass noodles.

‘The state payment for my latest book was quite good,’ the young woman said. ‘One thousand dollars.’

‘You don’t say,’ S. murmured. She was disappointed in the amount, to be honest: things should be much worse in Lukashenko’s Belarus.

‘I should add it wasn’t in cash, of course,’ Valentina said. ‘Our authors are paid in copies of their own books.’ She took a generous helping of the glass noodles, followed by the chanterelles and couscous with sausage.

S. kept track of the glass noodles’ path around the table. Next to Valentina was a pleasant lesbian couple: the delicate Lisa, who wore combat boots and had spiked hair and a PhD in gender studies, and the extremely sarcastic Mathilda, a buxom young literary critic. They helped themselves to heaping portions of every dish, possibly taking more of the glass noodles with shrimp than any other. Entirely possible. Next to Mathilda was Line, a Norwegian woman who immediately, without partaking of any, passed the bowl of glass noodles on to Malkhaz, a demon-faced dramatist and Jaana’s fiancé who believed that Herta Müller receiving the Nobel Prize was one of the year’s greatest catastrophes. The Georgian man cast a disparaging glance at the shrimp, asked ‘Shto eto, ryba?’ , and spooned none onto his plate. He asked Jaana if she wanted any.

S. was in conversation with Mathilda about the aesthetic torment of writing reviews but was really trying to gauge Jaana’s reaction. She’d realized earlier that Jaana was an expert chef who persistently whipped up antagonizingly meticulous meals for her Georgian beau. S. wasn’t quite sure whether she wanted a semi-professional to try her failed culinary attempt. The Thai fish sauce and lime juice were certainly the roots of the evil and to blame for the entire flop, sucking the life out of the seafood and noodles down to the very last drop and souring them to a desiccative degree.

Jaana shook her head. It was a very confident indication and the Georgian set the bowl down on the table directly in front of his plate instead of passing it along to anyone else. For a while, he quietly munched on his chanterelles and omelet and sipped his wine. Then, he shook his head as well, put down his fork and knife, and simply glared at the glass noodles. S. was now chatting casually with Dagbjört about the woman’s bloody crime novels based on the Old Norse sagas while simultaneously eying the Georgian, who continued glaring at her dish with an increasingly dour look and increasingly resembled a devil descending into madness. He then shifted a candleholder and Jaana’s bowl of mashed potatoes, trying to make space in the center of the table to shove the bowl of ryba further away, but the gap wasn’t large enough. He scanned the rest of the table. Finally, his eyes settled on the bookshelf next to the table. It was narrow and packed with all kinds of ethnic cookbooks. The Georgian’s face contracted into the tiniest grimace, and he shook his head yet again. He then glanced back and noticed the wooden bench usually used to hold newspapers and magazines. He studied it for a few moments before decisively seizing the bowl of glass noodles and removing it from the table with a general’s victorious expression.

S. considered how to react. Seated onward from Anta were Dagbjört, Nina, Sofia, Kristine, Daniela, Pablo, and Irena. Irena was a Polish translator, gorgeous, with genteel manners and an emphatically British English accent. S.’s glass noodles hadn’t reached any of them.

She surveilled her bowl behind the Georgian’s back while telling a joke.

Valentina, who was cut off from the main conversation, stood up and announced to the Finn that it was a friend’s birthday and she had to leave to congratulate her over Skype. S. shot a look at the portly young woman’s plate. She hadn’t even nibbled on the heap of glass noodles – all the shrimp and chicken had been pushed neatly to the edge of the dish. The zone denoted the midden of her plate. Valentina thanked Jaana for the delicious meal, carried her plate to the bin clearly labeled GARBAGE, and dumped the untouched portion into the gaping receptacle. Jaana waved amiably to the young woman and the other nice people did the same.

S. stared fixedly at the glass noodles behind the Georgian’s back.

Lise and Mathilda ate their helpings of S.’s dish quietly and with no complaint. S. observed them. Yes, these girls were fine democrats with a sense of responsibility and civic duty. They indulged in the glass noodles with shrimp and chicken just as ravenously as they did the omelet, tuna salad, and chanterelle sauce. Nice, intelligent individuals who had visibly suffered in life in spite of everything. S. watched Lisa and Mathilda politely finish off their noodles and felt a palpable physical attraction to them both.

‘These mushrooms are absolutely marvelous! What kind are they?’ asked the Norwegian travel writer Line.

‘Chanterelles, dark chanterelles,’ Jaana proudly replied.

Nina picked up the bowl of chanterelle sauce and ladled seconds onto her plate. ‘Oh! When I saw them before they were cooked, I thought they were just ordinary fungi!’ she said. ‘I’d have never dared to pick them myself. But our Jaana here is a true mycologist: it’s truly spectacular what you’ve made of them! My compliments to the chef!’

‘Yes, indeed – these mushrooms are divine!’

‘Incredible!’

‘Scrumptious!’

‘Amazing!’

Everyone commented on the mushrooms. ‘Yeah, great, definitely,’ S. said. She’d already had two extra helpings.

Would anyone else like some eco-parasites?

The bowl of glass noodles was still behind the Georgian’s back. S. opened another bottle of white wine and quickly filled her own glass.

‘Would anyone like some? It’s organic. Pinot Grigio.’

‘Organic wine is, well, how do I put this – the quality of organic wine is actually poorer than that of regular wine,’ Daniela said with an apologetic smile. Daniela’s boyfriend was a winemaker in the Moselle Valley. ‘First of all, they leave all the parasites in because they’re not allowed to use pesticides. And secondly, you can’t add the sulfites necessary for stabilization either . . .’

‘Yeah, yeah,’ S. interrupted. ‘Would anyone else like some eco-parasites?’

Daniela laughed. The Georgian theatrically shook his head.

S. wasn’t Herta Müller’s biggest fan either, but now she started to wonder whether the Georgian should really be picking fights on women’s issues. Malkhaz also glowered at the lesbian couple with his crazed demonic expression. Enough, God damn it! His reactionism had to be exposed!

‘So, Herta Müller is this year’s greatest catastrophe,’ she goaded him.

‘Yes. Awful.’

‘In what way?’

‘Awful.’ The Georgian used the Russian word uzhas. Another uzhas from a few years earlier was Elfriede Jelinek. When S. tried to pin him down on whether ‘uzhas‘ really just referred to someone being a woman, all she got was more uzhas. Uzhas this and uzhas that, no further explanation. Though Lessing, as it turned out, wasn’t so great of an uzhas.

‘Hey,’ S. said to him. ‘Could you hand me – there behind you – ?’

‘This?’ the Georgian asked, lifting the bowl of glass noodles from the bench in bewilderment.

‘Yes, thank you.’

S. confidently received the bowl and served herself another portion of glass noodles, shrimp, and chicken – poor, unloved salty creatures. And mung bean sprouts that once thrived in good faith, were later turned into glass noodles, and now sprawled awkwardly in the bowl. A cook bears enormous responsibility. Almost as much as a doctor. Certainly, as much as a history writer, who determines whether or not there is any point to a sacrifice.

Shrimp, chicken, shrimp. S. scooped up several mouthfuls. She washed them down with a swig of wine and wondered: what next? What to do with her dish? She could leave the bowl alone on the table and deny having had anything to do with it, renouncing authorship and simply enjoying the rest of the evening. Later, she could quietly empty it into the trash and that would be that. It wasn’t me. No such dish ever existed.

One can occasionally betray their creative works with glee. You don’t have to be a flagbearer who stands perpetually by your jumbled and complex associations, fervent poetry, sound-clusters, or abstract expressionism of youth. You don’t have to admit that you’re the one who was using Thai fish sauce in your cooking three hours ago. S. couldn’t tell if she even felt compassion for her dish anymore.

She set the bowl down in the center of the table. Not one hand reached out for it.

The concept of collective intelligence came to mind. No doubt this was it in practice. A decision materializes from the distinct, independent choices of different individuals and is often sounder than their choices taken separately. Signs of collective intelligence can commonly be observed in self-service dining establishments. It is collective taste-intelligence: multiple palates are multiple palates. The most popular dishes are usually the best: no one takes seconds of crap. Thus, some people intuitively pick out the finest morsels on their very first try. The bowl of glass noodles was still nearly full – only a fifth or so had disappeared.

S. spent a few minutes jabbing the noodles with the serving spoons. It was anybody’s guess if collective taste-intelligence was to blame. What would something like that mean, anyway? An ability to differentiate nuances, demonstrating the abundance of keys and buttons in your senses and showing off how finely you’ve been sculpted by nature or class? Hmm. There was an alternative interpretation: the glass noodles’ briny tang was simply too intense and complex for her tablemates, who were seeking relaxation from a light evening and simply refused to make the effort to enjoy them.

And now? Shouldn’t the phenomenon just be called a ‘boom’ instead of collective intelligence? One person exclaims: ‘Delicious!’ and everyone else follows in suit. It’s not as if the chef achieved a flavor that is physiologically intelligent and favors the organism’s survival.

Dagbjört’s omelet with bell peppers was as bland as bland could be, but it was still nearly finished off. What the hell, right? To be fair, it was a good, safe, old-fashioned dish; the favorite morning meal of anyone who grew up in a northern country; and Dagbjört herself was a congenial, motherly Valkyrie.

Sexism had to be the case here.

Pablo’s couscous with semi-processed meat: also scraped down to nearly the last crumb. Sexism had to be the case here. Who in the hell would gobble down couscous mixed with boiled sausage if the chef weren’t sparkling-eyed Pablo with his broad grin and knack for complimenting women?

These simple-minded, gullible squirts.

S. picked up her bowl of glass noodles again.

‘Did you two try this?’ she asked Pablo and Irena to her right. Pablo had meanwhile discovered that Irena spoke a little Spanish, which made him melt like butter.

‘No,’ he replied. ‘What is it?’

‘Glass noodles with shrimp and chicken.’

‘It looks quite interesting,’ Irena said in an accent that could have landed her a role in Midsomer Murders.

‘I’m afraid it came out a little too salty,’ S. said modestly.

‘Did you make it?” Pablo asked.

Both he and Irena took portions. And sampled them. Then ate.

‘No, it’s not too salty,’ said Irena, who had impeccable manners and began translating at seven o’clock each morning.

‘It’s actually very good,’ said Pablo.

‘It is delicious,’ Irena chimed in. S. smiled, charmed with a touch of melancholy. She’d finally heard the word directed at herself.

S. watched Pablo and Irena shovel down forkfuls of translucent mung bean noodles stained brown from fish sauce. Pablo’s expression was as rigid as that of a little bison, but no matter – he was urbane and empathetic in spirit. Affection engulfed S., giving her the urge to hug him. And the pretty little polyglot Irena – S. tried imagining if the young woman would abandon her adorable manners in the event of a theater fire or a shipwreck. Unlikely, apparently.

S. appreciated people like them. Nice, sensitive, delicate, intelligent people who’d no doubt encountered suffering in life. With them, you could build a truly tolerant and pluralist society where no one feels left out. S. lifted her glass and proclaimed: ‘Na zdrowie!’

Irena smiled. She was drinking water.

Neither she nor Pablo took any more of the glass noodles.

S. poured herself more wine. She hadn’t indulged in anything alcoholic for quite a while, going on long-distance runs every day and diligently typing something or another into her laptop to justify her grant. Now, she’d gone and cooked up a botched meal. There was reason aplenty to drink.

So, S. drank and chatted airily. The bottle of white ran out and she switched to red, S. was more of a red drinker by nature. She’d picked a bottle of organic Tempranillo with all its nice little parasites and zero sulfites.

When she studied the table again, she noticed that Nina’s tuna salad was almost as untouched as her own noodles. Nearly. Right then, Nina seized her bowl of tuna salad and started scooping heaps onto her plate.

‘I’m getting hungry again,’ she commented.

the junk would go down like she was a garbage disposal

‘Me, too,’ S. echoed, grabbing the glass noodles. She strained out the shrimp and chicken and filled half her plate with the salty mass. S. was sure she’d survive if she drank a lot of water on the side – the junk would go down like she was a garbage disposal. The categorical imperative of all cooks and creators.

S. ate, drank water and Tempranillo, and continued eating.

No. Shit. Inspecting the bowls once again, she had to admit that there was significantly less of Nina’s tuna salad remaining. There was no chance of catching up.

The others dug in again, too, reaching for the cooled grilled bell peppers and the darling lesbian chicks’ potato chips. Irena offered a batch of fresh cinnamon buns, which unleashed a new wave of ooh-ing and aah-ing. Delicious, wonderful, divine, mmm, aah, ooh. A series of gourmet-grubs’ orgasms.

S. poured herself more wine.

How nice all these people were. Endearing men and women of letters who deserved the very best destiny. She envisioned herself as the Roman Emperor Elagabalus, soon to smother her guests in a shower of rose petals.

S. caught the Icelandic writer’s eye and raised her glass, winking.

Dagbjört looked around the table, spotted the tuna salad, and spooned a couple heaps onto her plate.

Elagabalus only smiled and squinted.

After a while, S. realized she should cut herself off from the Tempranillo.

Pablo stood and announced that he needed to rise early to wrap up and submit an article on copyleft. ‘But thank you, everyone – it was all so good. This was a fantastic party!’

Lise and Mathilda also got to their feet. ‘Thanks. This was a genius idea, this party.’

S. followed, standing, and thanking the table.

‘Everything was delicious.’

She told them to keep partying till dawn and left.

S.’s room was hot. Some of the upstairs residents occasionally complained that their rooms were too chilly to translate or write in peace. She had never encountered that problem, though she was generally sensitive to cold. This, however, was unbearably stuffy. She opened a window before crawling into bed.

Beneath the blanket, it was like a sultry August night on the Mediterranean instead of October on an island amidst the Baltic Sea.

And her hands. They stunk. The reek of Thai fish sauce and garlic was almost unbearable. S. stuck them under the pillow, but the smell still seeped through. Shrimp, garlic, fish sauce. How far could she keep her hands from her nose? One option was to arc her neck back and extend her arms out to the side. But the smell would still find her; there was no escape. After a while the whole bed, and subsequently the entire room, became steeped in the combination of shrimp, chicken, sauce, and garlic. They were the astral projections of unfortunate creatures; the specters of the scorned, screaming, orange and voiceless in the space.

S. tried to remain blissfully still, imagining that she was a stone.

S. tried to remain blissfully still, imagining that she was a stone. A stone on a beach. Everything was fine so long as she didn’t move, or so long as she imperceptibly shifted. But as soon as she closed her eyes, she saw a bluish glass bowl brimming with translucent slop; tortured, shriveled shrimp; and soured chicken. The bowl had probably been put in the fridge and was already making the other leftovers stink. Soon, people would ask: wait, what’s this here? Who the heck made this?

It’d have been so simple to cook something small and elegant. Something uncomplicated that everyone enjoys. S. had missed the mark. What does everyone enjoy? Could she ever hit her target?

The white sheets around S. were salty. They contained some kind of salt; it was undeniable. Trisodium phosphate from laundry detergent. And salt that had soaked into the sheets from inside of her; the salt of Thai fish sauce.

Salt, sure, why not. Salt is a friend, it cleanses, it preserves, it’s so lovely you could write poetry about it. What would we do without salt? Our bodies would have no electricity. How gracefully the ions of potassium and sodium circulated through her body as she lay in bed, thinking about them. Whoosh. Do not fear salt. Salarium, salary, salad, what all else.

Enough. She got up and went to the window. Unforgivingly moist and chilly October air flooded into the room. For several minutes, S. stared at the neatly mowed lawn, the trees, and the church. She greedily inhaled the midnight-blue air, did a few silly breathing exercises, then turned on her laptop and googled ‘salt poisoning’. It turned out to be something deadly. All it took, according to one website, was consuming an amount equal to one one-thousandth of your body weight. That should be an ordinary cupful of salt in my case, 54 grams or so. Could my glass noodles plus all the other dishes have contained that much?

She’ll kick the bucket here in her private room, taking maybe two or three days, possibly even more before the others start to wonder: where did S. go? They’ll kick down the door and voila: a salt mummy!

It’ll be an immediate milestone for the writers’ house; a marker in its history. ‘Oh, that was the same year a stupid author was killed by her own salty dish.’ That’s what they’ll start saying. Maybe they’ll hire an official chef or have every guest sign a contract assuming liability for possible death if they prepared their own meals.

S. got down on the floor and started doing push-ups. Twenty-five, twenty-six, twenty-seven. Then a break. Good enough. Fifteen more. A full glass of water. Dizziness. Mhm. I’ll never get the grinding out of my body now. I’m composed of fragile, feverish pieces.

The shrimp and fish sauce were still clinging to her fingers, having started to transform her DNA.

A cold shower. That’s the ticket. She stood up, went to the bathroom, and opted for a lukewarm shower instead – cold water would be too jarring, even in a salt-fever. She dried off with a salt-colored towel and debated whether or not she felt any better. S. couldn’t tell. Her hands. She sniffed them. The shrimp and fish sauce were still clinging to her fingers, having started to transform her DNA. She stuck them under a stream of hot water and lathered them with shower gel and shampoo. After drying, they still stank of fish sauce and garlic. S. pilfered a big coffee mug from the downstairs kitchenette, filled it with water, and set it next to her bed.

The church bell rang on the half-hour. S. sipped water, closed her eyes occasionally, and had visions of white expanses peppered with dried corpses. The bones were rough and covered in a film of light granules, broken from fragility. When the church bell rang five a.m., she got up, dressed, and went to the kitchen in the main house. The party was over. The light over the stove had been left on for the night, the table was cleared, and the dishwasher shushed softly. The smell of food hung in the air but the space itself was clean.

S. gulped down a large glass of water, took an orange from her food bin, and peeled it. She lifted the lid of the large trash can to throw away the scraps and saw it was filled to the brim with bloody paper towels. They were vividly crimson, alluring: S. had always enjoyed the sight of bloody tissues and handkerchiefs. Beneath the bloody sheets were shards of a blue glass bowl mixed with thick translucent glop and orange shrimp. S. snorted. She lifted the lid fully and stared down. Glop, shards, beautiful glowing blood. She giggled like a fool. The church bell boomed, and she giggled on.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maarja Kangro (b. 1973) is a poet, prose writer and librettist whose sharp, allusive and often darkly humorous work has made her one of Estonia’s most distinctive literary voices. Trained in English philology and active as a translator of Eco, Enzensberger and others, she emerged as a poet with A Devil on Tender Snow (2006), bringing with her a European literary sensibility, a keen ear for rhythm, and a taste for linguistic surprise. Her prose—witty, layered, and emotionally piercing—has twice earned her the Tuglas Prize. In 2024, she was elected chair of the Estonian Writers’ Union.

Glass Noodles was originally published in the collection Dantean hole (2013). Adam Cullen’s English translation also appeared also in the second issue of the Baltic literary magazine No More Amber.