‘I did not want it.’

On the German edition of Karl Ristikivi’s The Night of Souls

The Night of Souls first came to me as a rumour. Every translator from Estonian I met, whenever the conversation turned to classics that ought to be available in German, soon mentioned the name Karl Ristikivi and almost always also the title of this novel that stands like a monolith at the centre of his oeuvre: The Night of Souls (Hingede öö). I was assured that this novel holds a special place in Estonian literature, representing its connection to European modernism – to Franz Kafka and Albert Camus, to Hans Henny Jahnn and Jean Cocteau. When people spoke of this legendary novel, even Dante Alighieri’s descent into the underworld or Lewis Carroll’s world behind the looking-glass didn’t seem far off. A reach into the upper register of novelistic art not only of the 20th century, then. It is a common practice to emphasize the status of a work by comparing it to works from other linguistic traditions: every country has its ‘Estonian Camus’ or ‘Bulgarian Joyce’, its ‘Icelandic Kafka’, ‘Slovenian Woolf’ or ‘Greenlandic Proust’ – a rhetorical device that need not imply that the literary altitude or indeed the commercial viability of the authors is, in fact, comparable.

Despite my caution, despite my restraint – my own desire to read is one of the main driving forces behind my publishing house: the wish to access texts considered classics in their original language that have yet to be made available in German – I could not resist. Maximilian Murmann embarked on a journey for me into Ristikivi’s realm and translated the novel Die Nacht der Seelen. By happy chance, I met Rein Raud (I still remember how he was introduced to me as a ‘Baltic universal genius’), who agreed without hesitation to contribute a thoughtful afterword that helps us German readers to contextualize this extraordinary Estonian novel.

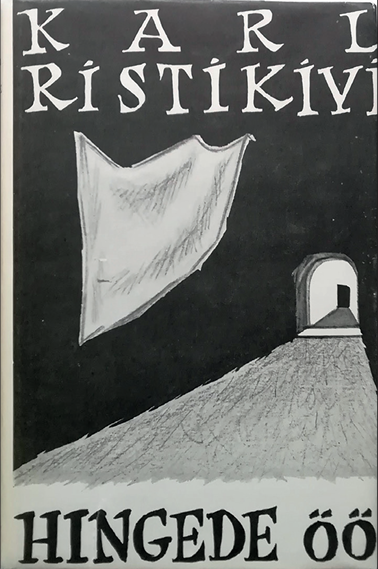

(1953), designed by Karin Luts

Within Ristikivi’s work, The Night of Souls marks a caesura, for nothing he had written before resembles this book and neither does anything that came after. A similar rupture is also found at the heart of the novel itself: on page 197 of 356 in Murmann’s German translation – which, in its dissecting clarity, paradoxically reveals the palimpsests and obscurities of the original almost too starkly – the first part ends with the phrase ‘NO ENTRY FOR STRANGERS!’ set in capital letters. It is immediately followed by a ten-page printed insert, the ‘Letter to Mrs Agnes Rohumaa’, in which a poetics of alogism is developed – a poetics of non-understanding. The key sentence, the one that responds to the letter writer’s question – why the novel shuns dramatic arcs, why it tells no story, why it circles around itself or rather an empty core without direction, purpose or sense – is this, stark and brief: ‘I did not want it.’ On the one hand, it evokes the absurd refusal of Herman Melville’s Bartleby; but on the other, it is equally a powerful declaration of creative intent. I, the author – the one who conceived and wrote the novel – I want it this way. And no other. That explains everything; that is what gives the work its validity.

I had already been prepared for this moment by the aforementioned rumours surrounding the novel. I was told to expect something in the reading that exists in no other novel in quite the same form. Yet when the translation was complete and I was able to read it through in one sitting, it hit me directly. And it still does today, five years after I published it, when I open the book and return to the letter. I can still hardly believe how lucid and electric that letter is – oscillating between fictional or fictionalized misdirection and sincere poetic testimony – how it simply stands there in the middle of the novel. Is Ristikivi sabotaging himself, interrupting his own voice because he no longer trusts his path? Or is it, on the contrary, a gesture of supreme sovereignty? Is the act of creation so absolute that the author can afford to rupture the illusion, to allow ‘reality’ to intrude upon the fiction, thereby rendering the construction of the novel even more unassailable by means of this incorporated disruption? I have never arrived at a satisfactory solution to this puzzle, but the journey of trying to understand it proves fruitful every time.

What is extraordinary is not only Karl Ristikivi’s formal boldness – his audacity in confronting us, the readers, with ourselves in the middle of reading; catching us off guard with our own emotions and reactions, where we normally feel safe and unobserved – just as striking is the emotional core of the novel, which lies in its portrayal of the consciousness of an exile, a condition that still (or again) speaks directly to us today. I would describe it as an experience of existential dislocation, perhaps even of being overwhelmed, along with a retreat into and encapsulation within the history of one’s own emotions. It is, in all likelihood, not voluntary or self-determined at all, but rather a form of entanglement, a state of captivity within one’s own story.

The narrative proceeds according to a dream logic: reality is not depicted but absorbed into the fiction, transferred from one sphere to another, just as dreams do with their dream-narratives. It is references, memories and associations that cross the boundaries between worlds – between reality and fiction or dream – and bind them together. The narrator of The Night of Souls, who hides behind the mask of the ‘author’ (or is it the other way around, the author hiding behind the mask of the ‘narrator’?) offers, in the guise of a question, the novel’s decisive answer: ‘In the end, is not everything imagined in literature a dream, dreamed by both author and reader, although they are not asleep?’

Literature – with its shimmering ambivalence and endless wealth of language and narrative that demands ever-renewed interpretation – lies behind one of the two doors evoked in the epigraph Ristikivi borrowed from the Finnish poet Uuno Kailas. Ristikivi throws this door wide open and invites us to step through with him: ‘So I have but two doors, / to dream and death they lead.’ The second, the other door, leads to stillness, to surrender, to the great immobility of death.

Sleep – or rather sleepwalking – connects The Night of Souls with another central, monolithic work of world literature: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. At first glance the two books appear to have little in common. Mann’s novel takes place on the eve of the First World War in a Swiss sanatorium removed from the everyday world, isolated and weakened by its characters’ suffering – from their neuroses and, yes, from the perceived meaninglessness of their own existence. Hans Castorp and the other guests become entangled in, and exhausted by, ideological and philosophical debates and digressions. The novel ends in a ‘turning point in time’, leading directly into a wartime society.

The situation in The Night of Souls is almost a mirror image: war, exile and the loss of homeland lie in the protagonist’s past. His life is marked not by a lack of experience but rather by an excess of it. Memories and unfinished threads catch up with him and flood him with impressions and encounters from his past. And yet, like Hans Castorp and his companions in Mann’s novel, he, too, reflects and becomes entangled in verbal skirmishes and exchanges with the characters from his own history – those he meets in the endless corridors and ever-deepening recesses of the ‘House of the Dead Man’.

‘In a war, there are inevitably two sides: one that starts the war and another that defends itself. Since one side alone cannot wage a war, the aggressor is entirely innocent. The one who defends is guilty, for it is only through them that war becomes reality,’ says Pastor Roth in the second part of The Night of Souls, in the chapter ‘The Sixth Witness’, which addresses the deadly sin of wrath – and one is reminded of the events in early 2025 in the Oval Office surrounding Volodymyr Zelensky, when the Ukrainian president, in a demonic twist freed of all reason, suddenly found himself being labelled a dictator. The humour in The Night of Souls, and the at times disconcerting relief it brings, is a vital aspect I must not neglect to mention. The wit and sometimes almost slapstick comedy – which arises equally from helplessness and from acute exaggeration, as in the Pastor Roth scene – carries us as readers through the novel, shielding us from both pathos and sentimental pity. That is why The Night of Souls still feels so fresh and surprising today, resonating in places with our present. And that is why I hope its discovery will continue across more languages, for only when it is translated into our languages can the world begin to recognize what a visionary, intense and profoundly European novel we have been gifted from the north-eastern edge of the continent.

Sebastian Guggolz

Translated from German by Yvonne Bindrim

EXCERPT

Excerpt from The Night of Souls in EstLit Spring 2025.

Sebastian Guggolz

Sebastian Guggolz (b. 1982) is the founder of Guggolz Verlag, a publishing house which specializes in new translations of works from the first half of the 20th century by forgotten authors from Northern and Eastern Europe.