Although Mudlum (born 1966) entered the literary scene late – just over a decade ago – she has become an undeniable and inimitable force in Estonian literature. Her debut, the short story collection Tõsine inimene (A Serious Person, 2014), which mainly gathered texts first published on the playful blog of the literary group ZA/UM, later internationally known as the creative collective behind the video game Disco Elysium, instantly won readers’ hearts. Since then, she has written a mix of novels, novellas and short stories while also establishing herself as a prolific and sharp-witted critic. She is the only person in Estonian literary history to have received the Cultural Endowment’s Prose Award two years in a row, first for Poola poisid (Polish Boys, 2019), a novel about the dreams of youth and how they are swept away by the realities of adulthood – which also won the European Union Prize for Literature – and then for Mitte ainult minu tädi Ellen (Not Only My Aunt Ellen), a searingly honest and painful narrative about the life, illness and death of her aunt, Ellen Noot – famous as the third wife of writer Juhan Smuul – and the process of coming to terms with it all.

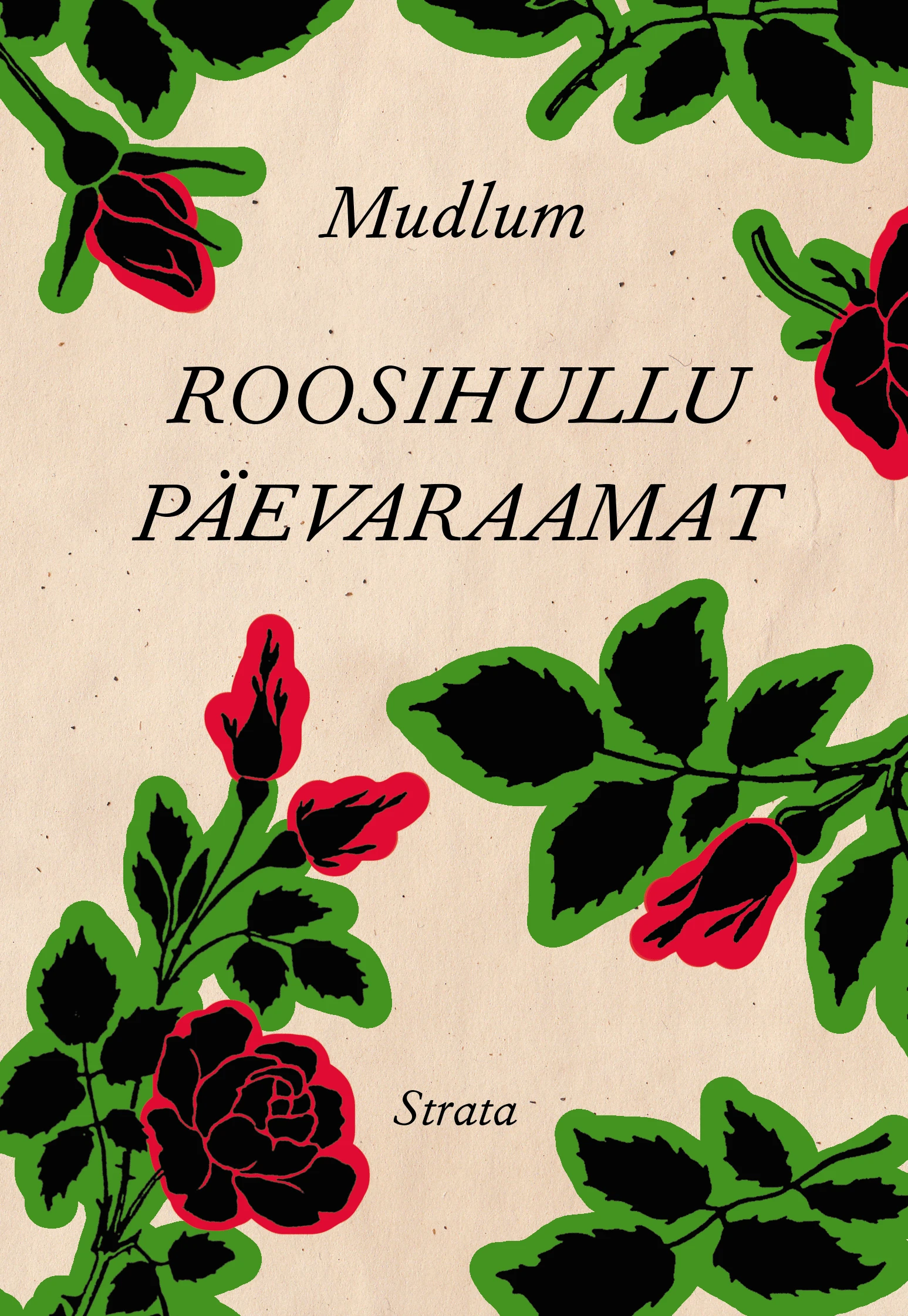

Diary of a Rose Lunatic (Roosihullu päevaraamat, 2024) appears at first to concern itself with the little things – bridges, crocuses, pansies, rain showers, droughts, autumn asters, galoshes, pruning shears, floribundas, phlox, garden hoses, aprons, wild orchids, sweet grass and roses – such everyday things, in fact, that the reader may begin to wonder whether this is literature at all. This impression is reinforced by the book’s diary format and the author’s deliberately amateurish ink drawings of her surroundings: a dachshund, coastal reeds, washing drying on a line, yarrow, the door of an old granary. Even the book’s design seems to steer us in that direction. With its yellowed pages, large notebook-like format, nostalgic rose motifs and dirt-smudged, thumbed pages, the book feels like a bundle of personal garden notes found in some attic rather than a work of fiction.

But this is deceptive. There is something oddly expansive in every sentence, between the lists of seedlings and flower beds – glimpses of the wider world. Each page might appear to recount nothing more than the daily chores, yet beneath the surface lies a contemplation of life and death, of the human life cycle, of the overwhelming power of nature and how helplsessly small we are in the face of it, of fate and our attempts to come to terms with it. Every ink drawing revives a strand of the Estonian literary tradition; each chapter contains a fragment of Estonian history. So yes, this is a book about a garden, but, as literary scholar Elle-Mari Talivee puts it, ‘garden books always end up being about people’.

Heli Allik