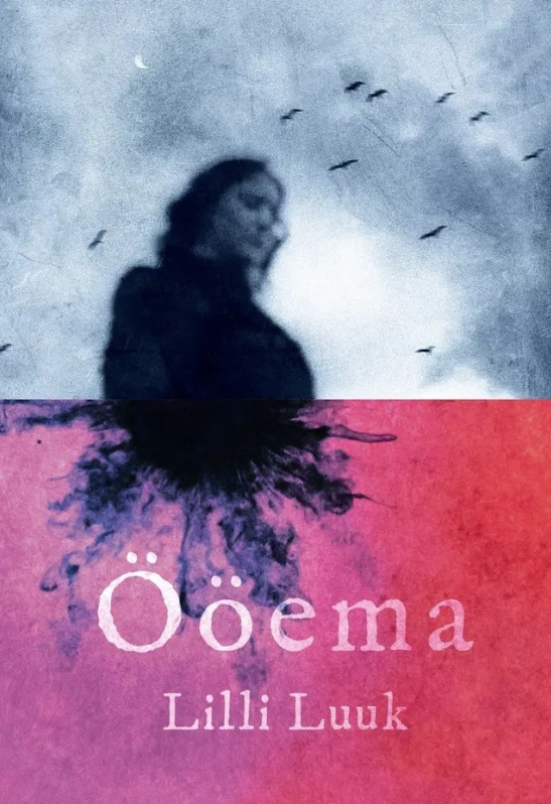

To date, Lilli Luuk (born 1976) has published three works: a collection of short fiction, Miss Collective Farm, and two novels, My Brother’s Body and Night Mother. Luuk has recently received the annual national culture award.

Luuk does not shy away from dealing with complex themes in her works – death, war, occupation and the transmission of generational traumas are just some of the motifs that the writer, with the help of sensitive and aesthetic language, weaves into her narratives. However, the impression of painful places is purposeful and instrumental – Luuk confronts readers with the complex heritage of memory culture, encouraging them to process an experience and take lessons from it. As she herself has described her role as a writer: ‘Literature can also be a tool for remembering things we don’t really want to. […] I may be the one who is recalling bad memories.’ [1]

The importance of remembering (as well as keeping quiet) is at the forefront of the Night Mother narrative. In this multi-voiced work, stories of violence, grief, and despair are steeped in the tales of women from different generations, reminding the reader that in the shadow of any grand narrative known from history textbooks, there are countless stories that have not been put on paper, written instead only in the population of future generations. As a writer, Luuk seems to have aimed to give concrete (written) form, and therefore power, to those silent stories.

Luuk has given voice to ordinary women whose experiences and contributions to history have often been neglected. Traumas that tend to be suppressed or belittled in everyday life are placed, without any shame, at the centre of the narrative in Night Mother. They are not there for the reader’s voyeuristic pleasure, but rather to emphasise the importance of remembering the past in the journey of healing.

On the pages of Night Mother, a voice from the afterlife argues: ‘How can anyone remember us when our images are turning pale, the paper is decomposing; we will be extinguished one by one.’ (p. 43). One possible answer seems to be concealed in writing. In both of her published novels, Luuk has written stories that have proven too painful, dangerous, embarrassing, or otherwise impossible to talk about in real life. Breaking the silence, on the other hand, allows for a better understanding of oneself and one’s predecessors.

Diana Koit

Translated by Slade Carter

[1] https://www.sirp.ee/kes-on-lilli-luuk/