A Filthy, Slimy Age

How to write about what is not said and about what does not exist? Piret Raud knows, although I am not sure about others.

Raud’s book has, in itself, a fairly clear story, one that can be retold in quite simple sentences. A young girl named Lill Aruvee is growing up in a house full of artists. Her father is a painter who has fallen into disfavour due to social change. The girl is bullied at school, and she does not know whether art is really for her. In terms of plot, then, this is a classic Bildungsroman, complete with descriptions of school and a first unhappy love.

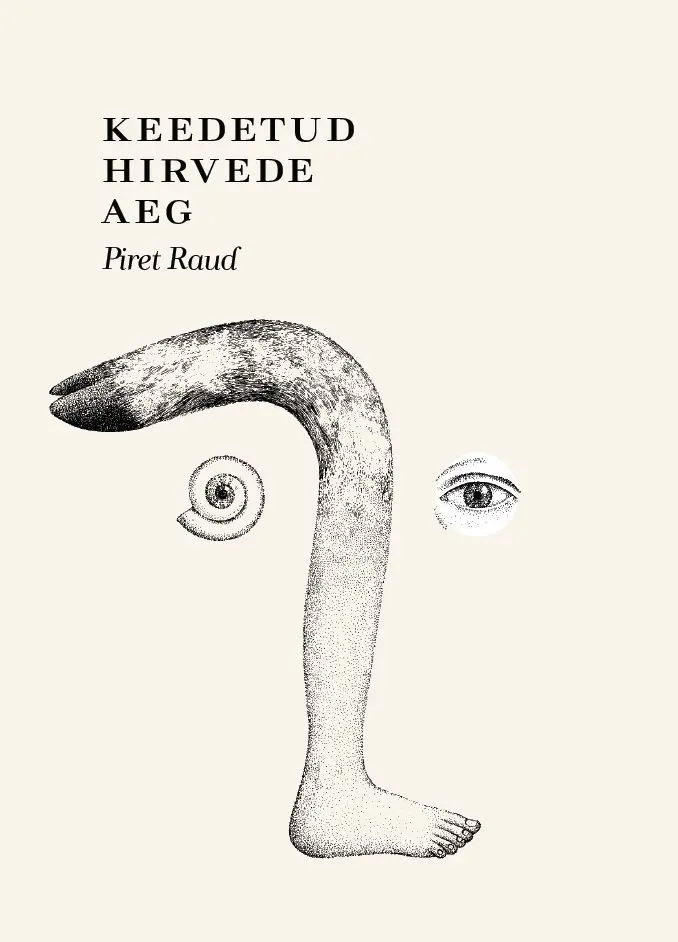

Yet Keedetud hirvede aeg (The Age of Boiled Deer), in recounting this story, repeatedly slips into dream logic: people are bolonkas (or vice versa?); the nameless city is struck by biblical disasters ranging from fires to floods; from the porthole window hidden behind the doughnut-seller’s stall a forbidden sea surges. Still, while reading, one feels an irresistible temptation to see this dreamlike, nameless city as Tallinn and the timeframe as the last gasp of the Estonian SSR.

Not everything the reader encounters can be explained by common sense. Raud’s world resembles that created by David Lynch. Through Raud’s city streets and beneath its floorboards swims an inexplicable tension and evil that can only be conveyed through devices familiar from the subconscious. Lynch is an appropriate comparison also because, despite Raud’s richly detailed language – which would inevitably suffer in any screen adaptation – the text unfolds as though it were a film. So vivid and powerful is the world Raud creates. She truly knows these characters and every hidden corner of the city.

A friend of mine, seeing the title of the book I was reading, reacted, ‘Boiled deer … revolting’. And indeed, the phrase ‘boiled deer’ is revolting, vile, slimy – something that should not exist at all. In the novel, the boiled deer remind Lill of the conformist, established works of the neighbouring artist Verlin, who has succumbed to the pressures of the age and allowed himself to be boiled through. What can one do? It was that kind of time.

Lill’s own father’s braver, unboiled art is hidden away in a basement locker where not even his daughter ever sees it. When a new time arrives (the open sea-border with its gulls and capitalism), another neighbour, Anderson, can calmly exhibit it in a gallery as his own. Because the art was underground, no one knows its true creator; the new era favours brazen frauds. Thus the coming of the new age (freedom, capitalism, the absence of censorship) is not unequivocally good – the former elite is simply replaced by another, and whoever wishes to belong must learn the rules of the new game.

Both Lill and her artist father take their art seriously; better not to engage in it at all than to make compromises and yield to external pressure. This does not mean it is painless or that it does not provoke envy to see others celebrated for adapting to the new world. Lill’s father explained to her why a raw egg spins more slowly than a boiled one: because within the unboiled egg there may be life, and life is in every sense clumsier than death. Keedetud hirvede aeg (The Age of Boiled Deer) explores precisely this clumsiness, which life inevitably entails – especially when one tries to live it true to oneself, whatever that may mean in one’s own time. Better to be clumsy than boiled.

Silvia Urgas

A shortened version of a review published in Vikerkaar (2025/6).