Early autumn

1.

Something had to happen.

This year, as with every other, there were many signs and predictions that convinced those who were ready for it. The autumn was extraordinarily rich in mushrooms; that many boleti had not been seen for a long time. An over-abundance of apples had grown, too: they dropped to the ground at night, and the canning factories and juicers were unable to process the yield, so great mounds of fruit were left to rot. Across the world, there were several airplane hijackings, with the crimes widely condemned and severely punished. Despite the growth in population, the afternoons were strangely quiet. All of this was reminiscent of life but still demanded vigilance, and Eero anticipated the evil as always.

On June 26, a driverless locomotive left a railway station near the city. Specifically, the driver or his assistant had briefly jumped off the moving engine and was unable to re-board. The locomotive broke through the barrier, up to the branch station, and from there to the main road leading to the city, against an incoming passenger train, which was travelling at some 80 kilometres an hour. But the other train driver kept his cool. Seeing the approaching engine, he managed to stop his train and put it into reverse. The locomotives only collided when their speeds were more or less the same. Consequently, an accident was prevented at the last moment. It happened a few days after Midsummer. But a few weeks later, another strange story took place.

They went to Southern Estonia for a colleague’s anniversary party in a beautiful forest village right by the Latvian border. Conversation flowed through the night, accompanied by some melancholy tunes by Bach, lured out of a flute by a tall, bearded man. Later, they went outside and listened to the nightingales’ strange lilting song as the light was rising. Nobody managed a minute’s sleep. It was still early in the morning, in the warm and bright light, when they set off. The host wanted to accompany them, but his wife would not let him go, just as it should be. The departure took place under a vast blue sky at six o’clock. The flowers smelled fragrant, but everyone had forgotten their common names, let alone their Latin ones. A bearded, former opera singer, a tenor who was known as Marino Marini, but whose real name was Mortenson, sang loudly in the fields and performed unsuitable arias, for example, the Queen of the Night for soprano from the Magic Flute, and the part where the Queen of the Night instructs Pamina to kill Sarastro. He soon tired himself out, his joy and mischief extinguished. He went gloomily beside his friends but refrained from calling out greetings like the others; he did not wish strength to the collective farm workers heading off to toil. Nor did he respond to the jokes made at his expense. The matter came to light at the railway station in Valga, which they finally reached to leave Southern Estonia by train. They bought their tickets and crossed the large, wide platform towards the train. However, halfway there, Marino Marini suddenly disappeared as if he had gone underground, soundlessly and right beside the others. It was as if he did not exist – an idea that naturally slipped through the tired minds of his companions. Nevertheless, they began to look for him, cheerfully at first, then with increasing fear, searching both the station building and the train. But Marini was not there. And so life goes, the friends thought fatalistically, and they went away. The opera singer had been missing for a few days – oh, the accusations his wife heaped upon his friends! – and Mortenson was already presumed dead when he emerged and told his story. Some sort of shadow had descended upon him. In the afternoon, he found himself deep inside Latvian territory. He had slept in an old village cemetery among the overgrown graves. The names of the dead were Latvian, Marino Marini said; that’s how I knew I was in a foreign place. However, since the border between Estonia and Latvia is open, no harm came from all of this. A kind-hearted collective farmer had taken him back to the Estonian border in his car. It turned out that the singer had walked nearly thirty-six kilometres in hot weather. It was generally believed that he was pathologically drunk. It’s a miracle that the Latvians didn’t shoot you, one of his friends said seriously, God knows what you told, sang, or asked them on the way. I think I was silent, Marino Marini supposed, I think I walked dumb and blind until the coolness of the cemetery lulled me to sleep.

At the same time, an earthquake occurred in China. Earthquakes had already taken place in Guatemala, the Kermadec Islands, and the Trial Islands. A Palestinian camp fell in Beirut, and tens of thousands of people were killed. The earth did not shake in Estonia that year, but a television competition was organised to find new Estonian writers because they had become so few; until then, the small nation could boast a large number of writers. Nevertheless, hope was not lost: 296 young writers responded to the television call, 18% of them boys and 82% girls.

Near the city, a group of artistic objects was placed on an open landscape, which aroused universal interest. Sven Grünberg’s band played the opening.[1] Eero also attended the opening of the assemblage of objects. He looked fondly at the pipes that were dug into the ground and painted with red stripes. He enjoyed the moving and flickering things. Some of them emitted a noise. They instilled a feeling of openness and freedom in the artistic Eero. Looking at the fountain-shaped piece that spouted real water, Eero felt an irresistible urge to realise his new inner freedom in external spontaneity and drink from the object’s tempting spout. He did so, but noticed that afterwards the flow of water decreased, the object now trickling instead of spurting. Eero realised later that the installation had a closed circular flow and that the object was not connected to the water supply. Eero had spoiled the object’s natural labours with his own natural behaviour. A sort of rift arose between Eero and modern art as he left the objects and walked along the country lanes towards the city.

Eero himself was a poet. He composed poetry but didn’t know who for. It was said in the reviews that his poetry often lacked an ‘address’. This caused Eero serious concern. The absence of an address wasn’t the issue. He himself had an address, the address of the sender, but he did not know the address of the recipient. The streets were full of people, though Eero didn’t dare ask them if they had read his poetry and what they really thought of it. He was afraid of a negative response.

On 6 July, 500 years had passed since the death of the German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Regiomontanus. True, Eero didn’t know astronomy, though he had tried to learn the basics once at university, he had left the course unfinished. Thus, Regiomontanus’s jubilee, a day so important to some, meant nothing to him.

He lived in the centre of Mustamäe, on the sixth floor of a large panel apartment building right in the middle of many other similar buildings, along with several hundred other people.[2] These people were unknown to him, except for some of the more interesting ones he sometimes encountered outside, some of the more personable folk, who he remembered from on the street in front of the building, outside, or in the lift. (He had once been stuck in the lift with a married couple for two hours, all experiencing a collective lack of air and a common gastrointestinal issue, unknown which was the more embarrassing of the two.) Each of these familiar acquaintances knew him, too, but did not show it outwardly, and Eero responded in kind. There was one particularly kindly looking old man whom Eero had persistently tried to greet at first, he had no idea why, but the old man was distrustful and didn’t answer, and before long, Eero gave up – why scare a nice old man with a hello?

Thus, Eero considered his surroundings principally as a landscape saturated with moving figures.

True, sometimes life made itself known. There was shouting from time to time, with one person shouting at another, or a plane would fly over low and flash its lights. The district was fairly quiet, though. A big highway passed behind the buildings, so the roar of the engines could not be heard on the grounds of the estate. In winter, it was quiet because the children stayed indoors. Sometimes when he opened the window, Eero smelled the scent of people. When the window of the apartment below him was open, the scent of warmth, perfume, and soup rose from it. Someone lived there. Yet nothing else was known about them. Someone lived behind the wall, as well as above. But they were all silent. Eero noticed that people were relatively quiet in general. They rarely shout. No one had screamed under, next to, or on top of Eero, ever. The panel buildings were very large, but Eero wholly agreed with the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard that though these buildings are large, it cannot be said that they are tall, because they lack a vertical dimension, one of the most important things that makes a house a house. Namely, they don’t have a basement where rats, snakes, dragons, and other deep psychological and chthonic creatures would crawl. Nor do they have attics, where the proximity of the sky evokes lofty thoughts, where a free spirit might live in a garret. The apartments are simply stacked one on top of the other. And since the buildings are compact and firmly attached to the ground, they do not depend on the environment and have no connection with the universe. The walls of these houses are not shaken by storms. Thunderstorms do not carry away their roofs.

Still, Eero loved to look at the monsters that he invariably found in his field of vision every morning. He felt a certain gentleness towards them when he simply took them as nameless large objects in different light and different weather. After all, the human was excluded, the individual was not part of the mix, tastes had no role, only pure form remained. Great square boxes in the fields, enormous, monumental sculptures. Eero was not an anti-urbanist. He didn’t long for the ducks to return. He found moods and secrets in the neighbourhood. He watched the shadow play rise and fall on the rough-panelled walls. He found that the universe indirectly betrays itself here too and is gentle against the crudest texture. Eero did not despise the city as such. In the city, he found its beguiling, haunting rhythm, its powerful tension, its bitter joys. Wasn’t that the world too? One could visit the pyramids in Egypt or see the Eiffel Tower – yet experiences could still be had here in this city. It was only necessary to be a little sensitive, to open yourself slightly to the world around. It was necessary to go to the window.

The panels dazzled Eero on a hot summer day, like the white desert cities of the Sahara, which Eero had never visited, but ample of which he had seen in his mind’s eye. In the evening, the panels withered, offering up a feast of tonal experiences. Sometimes, the sun shone directly on the buildings, but behind them, the sky was black from a rising thundercloud. The building stood like a white island of hope in the face of destruction and chaos. Sometimes at sundown, the black silhouette of the building was terrifying, with its urban brutality, evoking simultaneously sublime and morose thoughts. The buildings were strange after storms, sometimes spotted with snow, sometimes washed black with rain – like ruins or memories of long-dead cultures, like jungle cities after being excavated.

There was no shortage of secrets inside the buildings too. The lifts broke down and clattered on their unpredictable journeys; cats gazed at passers-by with burning eyes, and fresh names were added and erased from the name boards, each stranger than the next. In the stairwell, Eero sometimes had the feeling that someone might grab him from behind. A poetry reader, perhaps? He turned on all the lights ahead of him as well as those behind and only felt a sense of calm when he slipped happily into his apartment. Eero was absolutely certain that spirits – house spirits – lived in his building, though they only inhabited the common areas. Stairs and corridors were not sacred territory. When you were in them, you were not inside but still outside in the everyday world. What was outside was also unholy, and you could smell it: only cats would urinate there, marking their animal worlds. Instead, people were urinating in the elevator, which was an intermediate, neutral territory, a borderland where it was possible to encounter demons. These demons may not have been malevolent, and yet they could be very cunning at reworking a well-known idiom. They were so cunning that they did not take the usual known forms, preferring jumbled appearances and incarnations. The cricket had been replaced by the cockroach and the weasel by the rat. Some of the demons looked quite innocent before you figured out who they were. Many nations maintain in their mythology that house spirits are the embodied faces of the owners. Whose face then was that common mutt rummaging in the trash, whose face was that noble Siamese cat, the only one of its kind? The face of people. (For details, see E. Pomerantseva, Мифологические персонажи в русском олклоре. Moscow, 1975, p. 99.)[3]

Eero preferred to stay in his warm and comfortable apartment. There he did his work, which generated no real benefit for the people.

2.

August Kask lived in the same building as Eero, but on the ninth floor. His vantage point was high, and his field of vision wide. Eero did not know August Kask, and August Kask did not know Eero. They had probably met somewhere, but inconsequentially at first. August Kask did not limit himself to an impressionistic observation of his surroundings. He loved accuracy and had also generated statistics without anyone asking him to do so – besides his conscience.

An equally large building faced opposite his own. Counting from the bottom up, its windows were divided into nine rows (the building had nine floors), and while counting from left to right, there were thirty-two rows. Consequently, on this side of the building (on the side facing August Kask), there were two hundred and eighty-eight different rooms, just like August Kask’s building had on its side, facing that other building. (August Kask knew that his building had both sides, but the opposite building could have been painted. Merely a facade.) Two hundred and eighty-eight, in this case, if you count only the living rooms and do not include the exits, bathrooms, hallways and cupboards. Sixteen vertical rows also had balconies in front of the windows (a total of one hundred and forty-four balconies, and thus the same number of rooms with balconies). Laundry was usually drying on a couple of dozen balconies, and this number remained constant; only the specific balconies being used to dry the laundry altered – most of them could be used for this purpose, with clotheslines to hand. Special balcony flowers grew on forty-two balconies (some of them in the summer months alone, while others displayed annuals, or were brought indoors for the winter). Skis had been placed on twenty-five balconies (out of one hundred and forty-four). On four of the balconies, there were admirable attempts made to change the appearance of the space: a plant ascended a wide climbing frame, concealing the view, curtains drawn across the entire front of the balcony, etc. Mickey Mouse was probably drawn on the inner walls of three balconies for the children’s pleasure, or at least with them in mind. Adjacent to this building was a five-story one, with twenty rows of bay windows, meaning a hundred windows and a hundred living rooms on this side. The building had thirty rooms with balconies (on this side), but August Kask did not calculate other statistics about this structure, because a group of birch trees hid some of the windows from him. In total, August Kask could see eighteen buildings (including the roofs furthest away), seven of them five-stories and eleven were nine-stories in height. Lawn covered the space between the buildings, and the sky hovered above.

August Kask was a men’s barber. Almost every person has hair (here we don’t include those whose hair is falling out at some later date, or those who don’t get it cut). Hair colour depends on the same pigment as human skin, namely melanin: it determines the degree of darkness of the hair. Hair is usually black, light hair only occurs in some European and Australian peoples (but unequivocally white hair does not exist, even in albinos). August Kask loved his work, though unquestionably he did not know the mythological significance of hair. He didn’t know the Bible either, so did not have a clue about the story of Samson and Delilah. He knew that the hair of prisoners, soldiers, and students was cut in many civilizations, he had also heard that hair was cut at marriages, but he knew nothing of the archaic customs where the hair displaced their owner, or where it was necessary to pester the hair off the head in order to conquer a person’s soul. August Kask had spent his life cutting hair from men’s heads, but he had not saved any for himself. No one had taught him that. Of course, August Kask would have been shocked to hear that psychoanalysts even considered hair to be symbols of the genitals and thought that cutting off hair amounted to controlling and suppressing basic aggressive impulses, or, to put it bluntly, castration. (See C. Berg, The Unconscious Significance of Hair. London, 1951). Incidentally, some other authors believed hair to be a more universal symbol, not at all sexual, and that the ritual haircut is a conditional human sacrifice, especially because the soul resides in the head. (See G. A. Wilken, Über das Haaropfer. Revue coloniale internationale. Amsterdam, 1886.) Later, this whole set of observed problems used a completely different terminology called the haircut, a certain act of communication with a striking social meaning, and it has been said that the magical power of the hair comes from its ritual context but not the other way around. (See E. Leach, Magical Hair, in Myth and Cosmos, ed. J. Middleton.) Hair had always been a dark object; interpret that as you will. From Greek mythology we know of gorgons who had snakes instead of hair. When one of them, Medusa, was beheaded (a thing worse than a haircut), the snake hair still radiated power. However, as stated earlier, August Kask had no idea about any of this. He was a person with a realistic view of life who did not care about secret goings-on or witchcraft. He would have been sent to the devil if he had told such stories. He simply set about his daily work.

Nevertheless, he did have some interesting professional observations. At the end of the sixties, he had less work. Younger men and boys no longer visited him. Some of them did not cut their hair at all, some let their girlfriends and mothers cut their hair, which is why August Kask had less work over the next five years. Of course, the middle generation still went to the barber, even having their beards shaved and cologne splashed on their faces, but the absence of youth was still very noticeable. August Kask did not know exactly what happened in the world during those five years. True, he read the newspaper regularly, but he did not know the things that were important for his profession. August Kask did not know how much ideological value his profession had acquired in the world at the end of the sixties. During the French Revolution, clothing carried an ideological meaning, and now a person and sometimes his fate was decided by the length of his hair. The police fulfilled the function of barbers. Citizens pounced on young people with scissors, and society sanctioned this self-righteousness. Public haircuts were performed, just as once they were tied to a post of shame or burned with a red-hot poker. There were cases where people were killed because of the length of their hair. Society subconsciously realised the nature of the challenge at hand. Men, especially bald ones, became terribly jealous. A special musical, ‘Hair’, appeared on stage. It became a common joke among the bourgeoisie: I don’t know if it’s a woman or a man? They were always very interested in that. But it wasn’t only the bourgeoisie. Theatre connoisseur Jan Kott saw a couple kissing in Copenhagen one night, and he couldn’t tell which one was which. But he based one of his concepts on it, which became world-famous and was discussed at conferences. August Kask was unaware of all this global hairdressing news. And even if he had known, he wouldn’t have been able to connect them with everything that was happening in the world, for example, in 1968 (student riots in Paris, the German Federal Republic and the USA, events in Czechoslovakia, the Red Guards’ book burning, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy). August Kask’s scissors clattered. His pulveriser squirted. He saw life in its concrete forms of expression. Men went to the barber shop less often.

In recent years, however, men’s barbers gradually started to get more work again. The madness was over. August Kask noticed that young people came to him once more and allowed themselves to be pruned. The world was reconciled, the impossible was no longer wanted. However, the youth protest movement had left some mark on the contemporary worldview. August Kask had to admit that, for a long time after the madness had passed, the average man still had slightly longer hair than usual. Over time, shaved heads, sideburns and electric curls appeared again. Millimetre haircuts became fashionable, men painted their lips and wore earrings. Another kind of madness was approaching, and August Kask, as a barber, felt it especially clearly as he stood high under that August sky at his sentinel post, his gaze cast upon doomed humanity. Afterwards, he ate porridge. He made porridge for himself for several days. No one bothered him. August Kask was a bachelor.

Translated by Slade Carter

[1] Translator’s note: Sven Grünberg (b. 1956), Estonian progressive rock composer and musician. Leader of the progressive rock band, Mess, whose musical style was at odds with Soviet ideology.

[2] Translator’s note: Mustamäe (meaning Black Hill), where much of the action in this book takes place, is a large-scale brutalist housing development in Tallinn, the Estonian capital. The building project was established in 1962 and completed in 1973.

[3] Translator’s note: ‘Mythological characters in Russian folklore’.

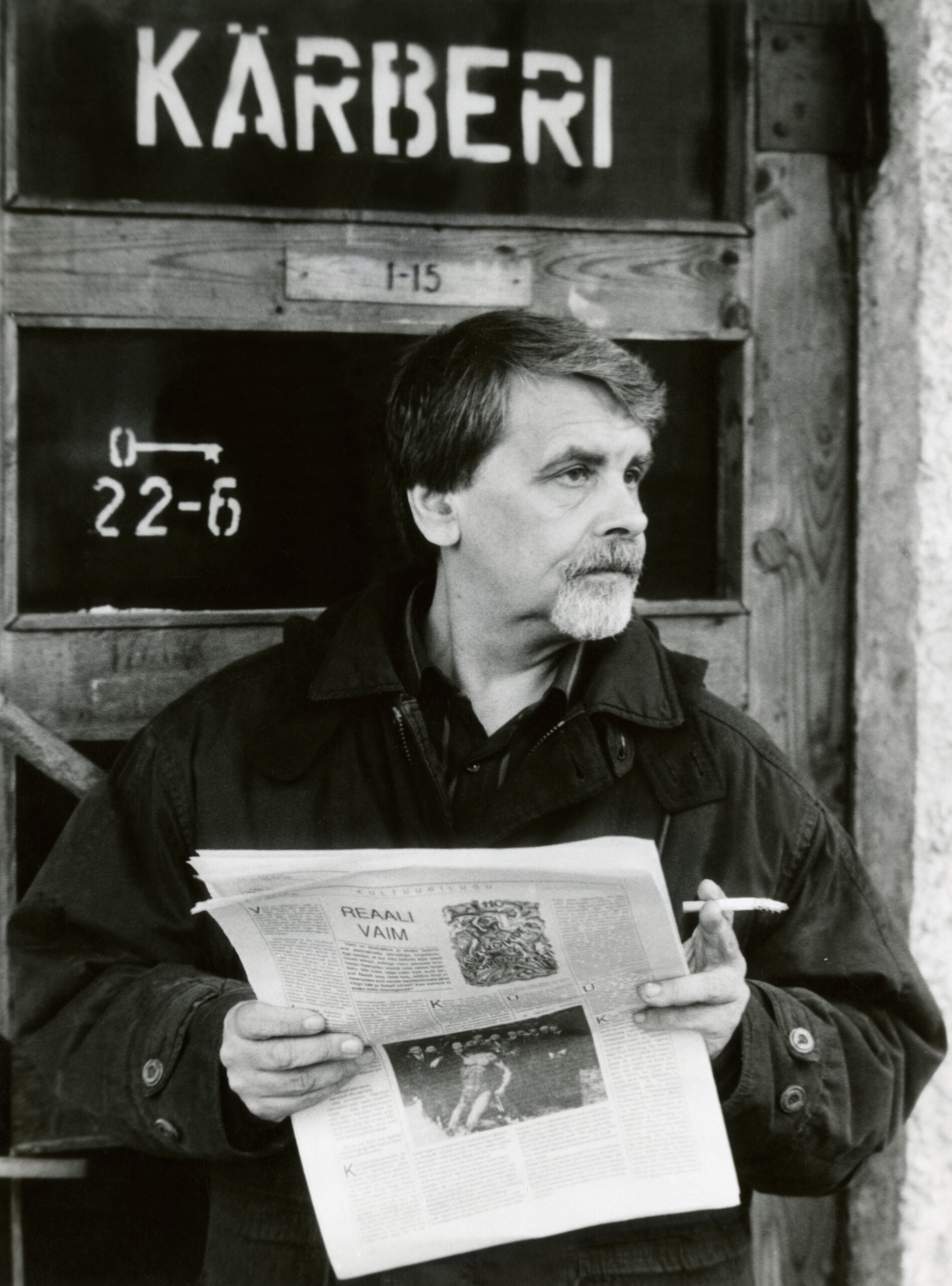

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mati Unt (1944–2005) was one of Estonia’s most enigmatic and inventive literary figures, bridging the worlds of modernist fiction, postmodern experimentation, and theatre. Emerging during the so-called Golden Sixties, Unt made an immediate impact with his debut Farewell, Yellow Cat (1963), which he later revised into Hello, Yellow Cat! – a gesture characteristic of his lifelong play with narrative, memory and form.

Though born in a rural area, Unt was a committed urbanist, and his fiction often captures the alienation and absurdity of Soviet-era city life. He brought to Estonian prose a new style –fragmented, ironic, philosophical – rich with references to Kafka, existentialism, and the grotesque. His characters typically inhabit liminal states, their lives punctuated by doubt, yearning and failed communication. In Autumn Ball (1979), perhaps his best-known novel, Unt paints a haunting portrait of disconnected lives in a Tallinn housing estate – bleak, intimate, and strikingly cinematic.