Kristjan Haljak: Given the nature of this publication, perhaps we should begin with the most fundamental question: why, and which works of Estonian literature, should be translated into other languages at all? Over a decade ago, you answered a very similar question in a popular weekly, saying that the book that should be translated into every language in the world is Legends of Old Pagan (Muistendid Vanapaganast, 1970). You added, however, that this would require a new, complete and literary edition.

It is also worth noting that you have just defended your long-gestating doctoral dissertation, The Cosmic Trickster in Estonian Mythology, in which you discussed Old Pagan and the literature surrounding him in considerable detail, closely linking him to Estonian place-lore.

So, in the spring of 2025, how do you see it now – why, how and what should be translated from Estonia ‘into every language in the world’? Do you still believe that Old Pagan is the trickster who could carve windows and doors for Estonian literature, landscape and mind into Europe, and indeed into world literature?

Hasso Krull: Translation is a form of discovery. A translation should contain something unknown – something unexpected or unforeseen – that the translator feels compelled to share because it was new to them. Sometimes translators doubt whether such sharing is even possible, and they try to soften the text, making it friendlier to the reader. Invisible commentaries creep in, and details that might cause unease or alienation are quietly removed. At other times, translators are convinced that no concessions should be made and may even twist their own language – its syntax and grammar – to echo the source language. The result can be a monster, a curiosity in its own right, understandable only if translated back into the original. Both extremes can diminish the element of discovery.

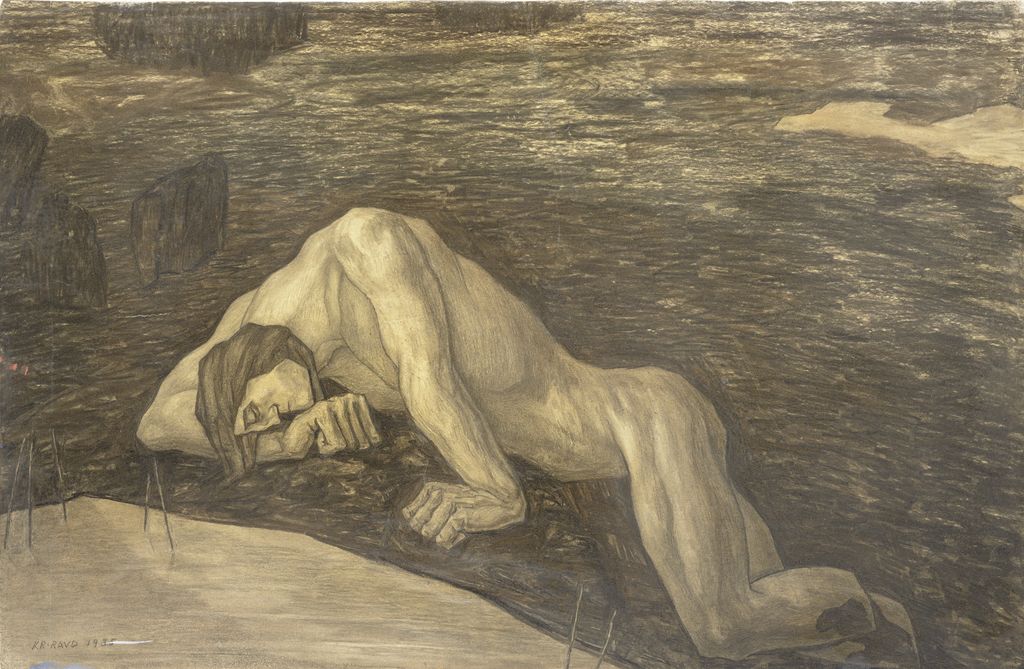

The trickster figure is so universal that readers will recognize them, no matter how strange or alien the details. In Estonian folklore, the trickster bears many names, most of them not true proper names, or else proper names that have become generic. The name ‘Vanapagan’ gained wider currency in the late nineteenth century, much like ‘Kalevipoeg’. Yet the character is always the same – he might just as well be called the Devil (Kurat), Judas or Jesus. Often he is simply ‘the strongman’ (vägimees). Nor is the trickster necessarily male: they can be female, gender-ambivalent, or not human at all – an otter, perhaps, or a bird flying over the sea. All these variations are broadly recognizable.

What, then, could make our trickster a genuine discovery for readers in other languages? The answer seems clear: only Estonian mythology, and the distinctive qualities of its mythological context, can do that.

In my view, translation is most compelling when the translator has discovered a text they simply cannot keep to themselves. Of course, this presupposes excellent language skills. But if skilled translators are few, then closer cooperation between translators, publishers and authors becomes essential. There are many authors; we must navigate among them, seeking strong points of reference. Here, introductions and well-chosen excerpts are invaluable.

KH: But how can the distinctive qualities of the Estonian mythological context be presented in a way that appeals to foreign readers? And can we even speak of a mythological ‘core’ unique to Estonian culture? Is the search for such a collective core necessary at all? Or might a well-curated fragmentarium prove more fruitful?

HK: The key is curiosity. Nothing can be made appealing without the pull of a receptive curiosity. We see this most clearly in children. A young child wants to try, explore, test and learn everything – parents must work hard to keep disaster at bay. At first, the child obeys readily enough, but with age comes a fascination for the forbidden: prohibition only fuels curiosity. Even at school, most children start out wanting to learn everything. But if they discover that school repeats the same kind of material endlessly, with no sense of direction, their interest drifts elsewhere. In all cases, curiosity is the engine.

In mythology, nothing can begin unless curiosity is stirred. Exactly how this happens cannot be predicted. But curiosity is contagious; it feeds on very little. Last year, one of Estonia’s publishing sensations was a complete new translation of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Was it because people yearned to read 800 pages of dense, complex prose? Of course not. People’s curiosity had simply been piqued – what is this thing everyone has been talking about for a hundred years? Surely there must be something in it! Curiosity is always built from two components: a spark of excitement and a scarcity of information. This is precisely how computer games work. Just watch how children play Minecraft or Roblox.

No mythology has a single, unique core. Mircea Eliade thought creation myths formed the core of mythology, but this is a very general definition – almost tautological – because if we did not distinguish primordial creation time from the present time, how could we recognize myths as myths? One could just as well say the core of mythology is myth itself. Yet myths reach us only in fragments; mythology is always already a literary rendering. Mythology can be unified; a myth cannot. And if the myth is the ‘core’, how can that core exist only in fragments?

I like Timothy Morton’s maxim that the sum of the parts is always greater than any whole. Myths can exist in so many variations that no single mythology can contain them all. But there is such a thing as a mythical field on which mythology rests. This field must be organized – by emphasizing certain moments, creating contrasts and so on.

In my view, the organizing principle of Estonian mythology is landscape. Mythology begins with the myth of the creation of the landscape, and the creation of landscape is itself a trick. That is why the trickster is so central. I do not claim that landscape creation is unique to Estonian mythology – that would be absurd – but the links between the trickster, creation and a certain kind of landscape in Estonia are especially fascinating. Through myth, the landscape becomes singular, and thus so does the myth. Today, this has clear implications for the ecology of the landscape. These implications, however, are not limited to Estonia – they extend to any landscape, for the ecology of landscape is universal.

KH: If, however, we do wish to speak of some kind of national literature – as the title of our journal, Estonian Literature, in its way demands – should we also trace connections between landscape and literature? Is this even relevant in the context of contemporary literature, or in 2025 is Estonian literature already independent of the Estonian landscape? And is it always dependent on the Estonian language? For example, the poems by Triin Paja that we published in this issue were written directly in English – although it is worth noting that she also writes masterful, enchanting poetry in Estonian. So how should we, in general, think about the relationship between landscape, language and literature?

HK: Landscape is literature. Folklore is oral literature – it is simply unwritten, at least until ethnologists or collectors of antiquities arrive. Reading the landscape is an act of literary interpretation, because the landscape can only be seen as landscape through tradition, and that tradition is always bound to storytelling. Narration is the axis of tradition. The Estonian landscape would not be ‘the Estonian landscape’ without Estonian tradition, without Estonian storytelling; in other words, the landscape is narrated into being, and the Estonian landscape is narrated into being as Estonian.

Other forms of literature in turn rest upon this storytelling. Much literature has been written in Estonian in exile, and it largely falls into two categories: on the one hand, the attempt to escape the Estonian landscape entirely, to move elsewhere (for example, Karl Ristikivi’s historical trilogies or Ilmar Laaban’s surrealist poetry); on the other, the attempt to regain the landscape by imagination, to recreate it in absentia (for example, Marie Under’s exile poetry or Bernard Kangro’s Tartu-focused novels). In the first case, new stories are sought in order to anchor new visions; in the second, there is a radical refusal to let go of the old story, whether out of nostalgia or because its power remains undiminished. In both cases, however, the narrative bound to the landscape remains the decisive weight on the scales.

This raises the question: is it inevitable to write about the Estonian landscape in Estonian – especially if the tradition is largely Estonian-based? Here, there are several caveats. First, the Estonian landscape has never been described or spoken of exclusively in Estonian. In the early nineteenth century, liberally minded Baltic German intellectuals developed an interest in local folklore; they gradually began collecting and describing it, and, of course, most publications appeared in German. Estonia’s first historical novel, Garlieb Merkel’s Wannem Ymanta (1802) – which has been called a ‘prose poem’ and whose subtitle is in fact A Latvian Saga (Eine Lettische Sage) – was likewise written in German. Friedrich Kreutzwald’s epic Kalewipoeg, eine Estnische Sage appeared in 1857–61 in a bilingual edition, and it is worth mentioning that the German text was of great importance to the author, who waited patiently for its translation to be completed. Bilingualism thus has a significant role in the Estonian literary tradition, and without it one cannot speak of the nineteenth-century Estonian landscape at all.

Second, if we equate language, literature and landscape, we create a very strong ideological chain of equivalence. It begins to seem as if one could not exist without the other two. From here, a kind of metaphysics of landscape begins to develop, assuming that a certain type of landscape gives rise to a certain type of tradition, and therefore a certain type of literature. The folklore of mountain peoples is different from that of steppe peoples; coastal folk tell different stories from those inland. But such an analogy cannot be carried too far. Rather, I would say that Estonia is a traditional ecological community in which language, literature and landscape create a vast and intricate network. Into this weave, other languages also fit, and many strands from other traditions extend. What matters is the cosmology that holds this network together. And here every strand is essential – from the oldest myths to Triin Paja’s poems in English.

–

HASSO KRULL (b. 1964) is an Estonian poet, essayist, and translator whose work bridges mythology, philosophy, and contemporary poetry. He has translated authors ranging from Jean Cocteau to Charles Bukowski. In 2024 he defended his doctoral thesis Cosmic Trickster of Estonian Mythology.

Poems by Hasso Krull in EstLit Spring 2025