THE DEAD MAN’S HOUSE

Chapter 1

The story I now wish to tell you began on New Year’s Eve, and it probably did not happen purely by chance, if anything can ever be excused by chance alone.

Along with midsummer celebrations, New Year’s Eve has always been one of the toughest. Yet it isn’t just the melancholy of spring turning to summer; it does not gust through open windows. It resides within you even before then, an iron-cold lump in the middle of the room. Its icy breath creeps outward from within. And so it has been for as long as I can remember.

The warmth of Christmas Eve when I was a child was so great that I never even noticed my legs grow numb from the cold. I’d stretch out on the straw and not find it chilly in the least, even though it had been brought in from outside according to old Estonian tradition. That was then. Later, one begins to take greater notice not only of whether the straw is warm or cold, but of whether it’s one’s own or belongs to a stranger. Later, it’s classified more as borrowing. (I don’t mean theft—this story is not a confession.) Borrowing once a year without any prospect of paying it back—that’s still alright, somehow. There aren’t as many years as there are days within a year, in any case. And that is why other nights must be endured by one’s own means.

Allow me to briefly explain why I was alone that night. I didn’t accept any acquaintances’ invitations to New Year’s celebrations, even though I received them. I can’t remember how I excused myself so as not to offend those making the kind offers. I’d resolved to get by on my own. I was sure to come up with something if I didn’t have the nerve to stay home and listen, in emptiness, to each of those twelve booming strokes that sound closer and louder with each passing year, until they ultimately deafen. Much worse can happen: the tolling of a bell can be deadly; a device that Dorothy Sayers used in one of her novels.

I went out. The people of this city ring out the old year in a variety of ways, not just in homes and restaurants. Upon leafing through newspapers or observing the pedestrians coursing down the sidewalks, one might even conclude that scant few remain home for the occasion. The easiest option is to go to the cinema, where it’s dark. It is a pleasant type of darkness, warm and protective like that which blankets a sleeping child. Everyone just sits in that blackness. Only the screen is white, though there are no people; only shadows. It creates a sense of equality. There are other opportunities as well, of course—excuses to sit peacefully in a crowd without anyone finding it unusual, each entertaining to some degree or another. Paid performers at least appear to do everything in their power to lift the audience into festive spirits. Though I’m not quite sure how they would react if they were to ever truly achieve it. The doorman in a blue coat with gold buttons, the vaktmästare who stands in the rear, certainly wouldn’t approve. He looks more like a customs agent keeping a sharp eye to ensure that no one brings in any contraband. I’ve attended those nighttime concerts on a couple of occasions. One was held at the Concert Hall, where the repertoire was more refined than the audience—applause broke out by mistake at one point during Grieg’s Piano Concerto. But when the concert ended and a loudspeaker blared the bells tolling midnight, I didn’t see a single person wish anyone else a happy New Year; I do not know whether it was forbidden or simply superfluous.

This year, however, I didn’t duck in anywhere: I stayed out on the street. I’d read so much about finding solitude in the primeval forest of a metropolis’ streets that I allowed myself to be led astray. It wasn’t long before I realized I’d made a grave mistake. People and cities are all so different, and what lifts the spirits with one can knock you off your feet with another.

It was as if I’d wandered into an insane asylum. (Insanity is a common theme among the encounters that have dealt me the greatest terror. I can remember the fear that gnawed at me as I walked past Kopli Cemetery after watching The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in the cinema. And not because it was a cemetery—it could have been any forest or empty lot.) The whole street, both the sidewalk and the roadway, was packed with young people both male and female, drifting around in large groups as they hollered, whooped, and blew paper trumpets. That last noise possessed a threatening and furtive idiocy that seemed to lie on the verge of crescendoing into an act of pointless violence. Still, it escalated no further than firecrackers for the time being.

I’d certainly imagined that the crowd would be jolly and puckish. And genuine, exuberant joy is not always expressed with the same grace and harmony as on an opera stage. But I saw not a single cheery face, not one happy person. A happy person feels no aching elbows; only a mourner might find the condition preferable. Yet I’d gone out in neither a state of sadness nor of joy—I’d left emptily, like a woman setting vessels outside before a downpour to collect soft rainwater. To develop that comparison further, I might say it was more like hail. They were dour, malevolent faces and hostile, scornful noises that were seemingly directed at the roisterers’ fellows, but in such a way that the sounds almost incidentally grazed each passing stranger. Some regard this as a form of humor, and who of us hasn’t laughed at those American-made farces where a cake meant for one target misses its mark by the slightest margin and hurtles into the face of a dignified lady just entering the room. These whoops hawked from the very back of the throat were just as purposefully misdirected from their presumed marks and I found it hard to appreciate the humorous angle given that, at the same time, all I could see was a hand clenched into a fist, and which remained a fist even when wrapped around a girl’s waist. I saw not a single smile, even though I heard laughter. The laughs themselves were more like phony ghostly whinnies—witless, beastly, and yet deliberate, charged with ample intelligent duplicity.

I honestly don’t wish to come off as exaggerating. It’s possible that I treated them unfairly; that I wasn’t as neutral as I would like to believe, a clean white page upon which all colors appear in their natural shades. When you’ve been a refugee for seven years, then it’s hard to suddenly lace up your boots one night and set out as a tourist . . . I say ‘seven years’ because the poetic ring to it lured me astray from the truth. In reality, my exile has lasted exponentially longer.

I’ve been trying to see the good in people for so long that the very first thing I do notice is inevitably something unpleasant. This isn’t as paradoxical as it may seem. And in no way does it mean that I’ve ever regarded someone with prejudice, much less hostility. It’s actually much easier to forge one’s way through a hostile world than to adopt the same attitude. On the contrary: I’d left home in a kind of mild, gentle Saturday mood, and although not quite deliberately, I was still semi-consciously seeking any sign of geniality; any inclusive smile or jest shouted across a crowd in a moment of carefree merriment for the free consumption of all—one that might have allowed me to feel like I, too, was a member of that gleeful company, if only fleetingly. It needn’t have been anything personal—like a joke cracked on stage, with which everyone in the auditorium may laugh along. Nothing of the sort happened. I played no part in that raucous current, apart from it dashing me painfully against an underwater rock here or there. Only my reaction to it differed that evening. Usually I’ve withdrawn, feeling either resigned or bitter, and gone home. But that night, I suddenly felt too weak to do so. I was incapable of activating that sole defense—flight.

I became afraid. I’d strayed too far from home to simply jog back. It wasn’t my first time being terrified, of course, but I’ve never experienced fear in the same manner since then. Perhaps ‘fear’ isn’t the right word—it’s difficult to find the proper term to adequately describe a psychological situation one has undergone for the very first time. It wasn’t ‘fear’ in the physical sense, and neither was it an apprehension of something to come. That sensation was already present, right there, surrounding me from all sides.

I’ve tried to sort through my memories and find anything equivalent. As a child, ghost stories that I’d either read or heard sometimes made me afraid of the dark. Hanging in Mihkel’s one-room sauna cottage was the vivid portrait of a Chinese man, of which I believe I was terrified—especially after Mihkel stepped on a sea mine washed ashore during the war and was blown to bits. I also remember the ambiguous dark terror that washed over me whenever I awoke from a half-forgotten dream and snuggled deeper beneath the covers—down into another darkness that was warm and protective. I can dimly recall once seeing a black dog that was apparently a fox. When I remark now that there was even a glimmer of enjoyment in that fear, I’m harking back to when I read Treasure Island and, just like the protagonist of about my age, thought I could still hear the parrot’s raspy cry of: “Pieces of eight! Pieces of eight!” But some unreal reason always lay behind the fear, because it was one that sprouted from fantasy. I’ve experienced it only twice since then, as more or less an adult: with the aforementioned Dr. Mabuse and with Dreiser’s Vampyr. Only on those two occasions, there was no definite impetus. Such fear can seem outright ridiculous if you consider much more consequential causes, such as bombs falling around you or a fresh manuscript’s fate when you have no more than twenty cents in your pocket to buy the stamp to send it. Yet at the same time, it is the emotion’s very real baselessness that does not impart the same degree of shame or force you to play the cold-blooded hero.

After a while, I could no longer bear it. The sensation turned physical and my legs became weak like when you are forced to climb a dream mountain. I had to get out of the icy, debilitating current as soon as possible. But plowing onward grew increasingly difficult. I felt that I couldn’t make it to the end of the street; that I didn’t have what it took to dash through the gauntlet. The street itself appeared endless—the chilly, garish glow of neon signs drew parallel lines that met in infinity and were drawn further by the darkness of the desolate overcast sky. I tried to escape by turning onto the very first cross street I came to. The idea was momentarily soothing—I’d found some solution, albeit temporary and still in close proximity to the source of my disquiet. I felt almost like a fugitive, pursued and afraid of being caught at any moment. Once again, there came a sensation of occupying forbidden territory, and the scorn and hatred of that crowd—profoundly physical like the icy wind blowing in my face—acquired a kind of personal nuance. And as soon as it happened, it also felt justified. I couldn’t defend myself, not even morally. I had absolutely no right to be there. The space I occupied with my earthly body was meant for others. I was a stranger, uninvited.

I hugged the very edge of the sidewalk, clinging to the buildings’ façades where I stumbled repeatedly on projecting stoops. But before the first wave of spiteful laughter faded in my ears, I arrived at a narrow lane that was almost pitch black and, as far as I could tell, deserted. Alas, it turned out to not be totally unoccupied. A young couple, boy and girl, their arms wrapped tightly around each other, jogged past and suddenly vanished, as if they’d gone through an invisible door and immediately pulled it shut behind them. I thought I glimpsed a street sign at the corner reading Era Tänav, ‘Private Street’, though it must have been a trick of the light because there was no way something could be named in my native Estonian here in this city.

In a way, the lane appeared closed in its entirety; turned to face the opposite direction. I inferred that it must be a dead end, which would explain the lack of passersby. Nearly every window was dark; only a couple of Christmas stars glittered in the upper stories further along. One pane reflected flickering candlelight, but I was unable to determine the source. The lower-level windows were shuttered or had heavy iron grating, leading me to believe they might be goldsmiths’ shops. The street itself was narrow, but the sidewalk was broad and level and, even in the darkness, I was able to discern a pattern of alternating light and dark tiles. My footfalls were the only sound, though the echo came with such a great delay that it felt as if someone were walking behind me. It was so deceiving at first that I kept looking back over my shoulder. Yet all I saw was the glow of the main street.

I cannot say I was immediately released of my fear in that alleyway. It trailed me at first, then seemed to lurk ahead. The sensation grew even deeper and darker, but a recklessness and audacity, equally incomprehensible and unfounded, rose to its surface. As a boy, I would sometimes fight the darkness by whistling. Now, however, I failed to produce a sound. I suddenly felt as if I were embarking on some kind of an adventure—one of a nature impossible to surmise, but which drew me to it irresistibly all the same. I even experienced a gentle sense of rising anticipation, almost impatience.

The street jogged slightly and, just as I rounded the bend, I glimpsed an unexpected river of light spilling from one of the houses. It came as such a surprise that I slowed my pace for a moment. Just then, I began to hear soft music that was likely drifting from the same dwelling. When I came to the radiant shaft, I could see it was pouring through a doorway that, contrary to the customs of city streets, was standing wide open.

I drew an immediate conclusion of the likely cause, which was slightly disappointing. No doubt it was the venue of a public New Year’s celebration—some cinema or tiny theater tucked away on a side street. The performance had certainly begun already, judging by the hour, which could also explain why no one was to be seen hurrying in the direction of that oasis.

I hoped I might nevertheless be able to step in for a short while. Seeing as how the door was left so invitingly ajar, one could reason that an auditorium in such an orphaned locale must not be sold out. At last, I could spend the year’s short hour or so still remaining encompassed by the luxury of light and warmth at the cost of a couple of Swedish krona. It would, of course, mean retreating from my earlier decision. But better to end the old year with the recognition of failure than to begin the new one with it.

And I walked through the open door.

The first chapter translated by Adam Cullen was originally published in the Baltic literary magazine No More Amber.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Karl Ristikivi (1912–1977) is one of Estonia’s most important 20th-century writers—a quiet master of psychological depth and historical vision. Writing much of his work in exile, he brought European culture, ethics and symbolism into Estonian literature, crafting novels that reflect both inner solitude and universal human questions. His style is restrained yet emotionally resonant, always marked by a deep sense of moral and spiritual inquiry.

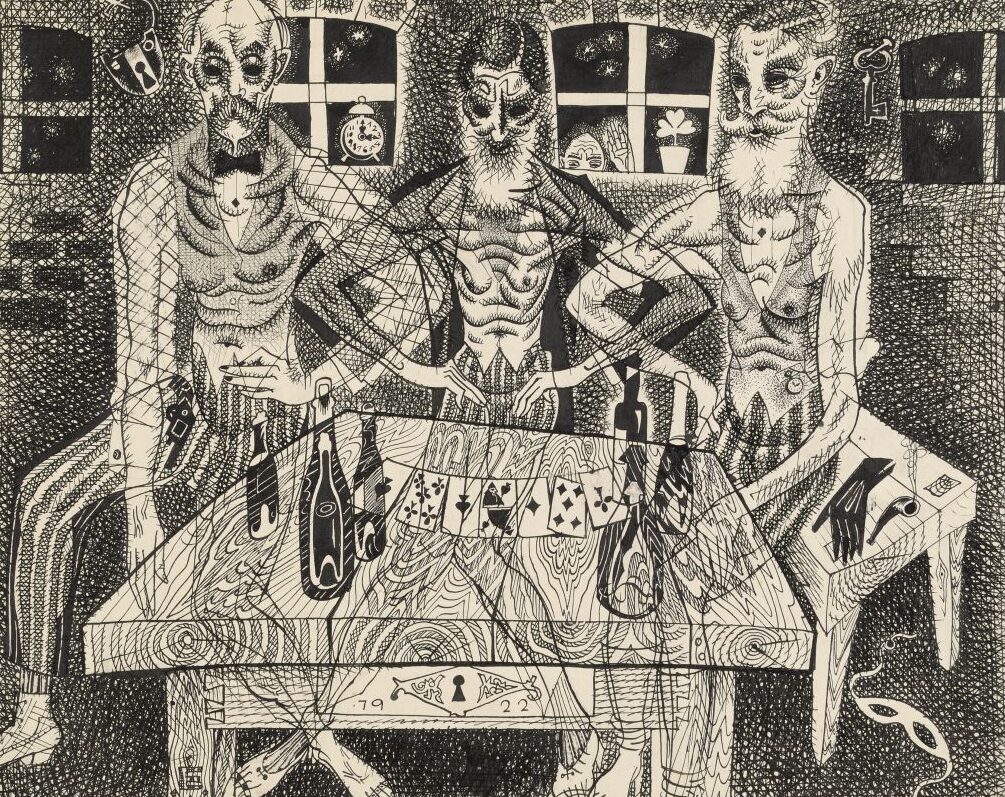

The Night of Souls (Hingede öö, 1953) is one of the most remarkable works of Estonian exile literature—an introspective, symbolic novel that marked a radical departure in Ristikivi’s career. In its dreamlike opening, a nameless man enters a mysterious building on New Year’s Eve, known only as the House of a Dead Man. As he moves from room to room, the atmosphere becomes increasingly strange and unsettling. Each encounter is theatrical, philosophical—leading deeper into a world where memory, morality and identity unravel.

Written in post-war Sweden, the novel trades realism for a modernist, surreal exploration of the human condition. Influenced by Kafka and Calderón, yet entirely Ristikivi’s own, it becomes a metaphysical journey through guilt, solitude and the search for meaning—culminating in a courtroom trial of the Seven Deadly Sins.