Urban Echoes: Rediscovering Mati Unt’s Autumn Ball as a Modern Classic

The literary modernist movement created its own genre for the city, whether it be John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer or Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz – novels that capture urban life in all its fragmentation, anonymity and existential coldness and which are still considered milestones of modern literature. Less well known, yet equally significant, is Mati Unt’s Sügisball.

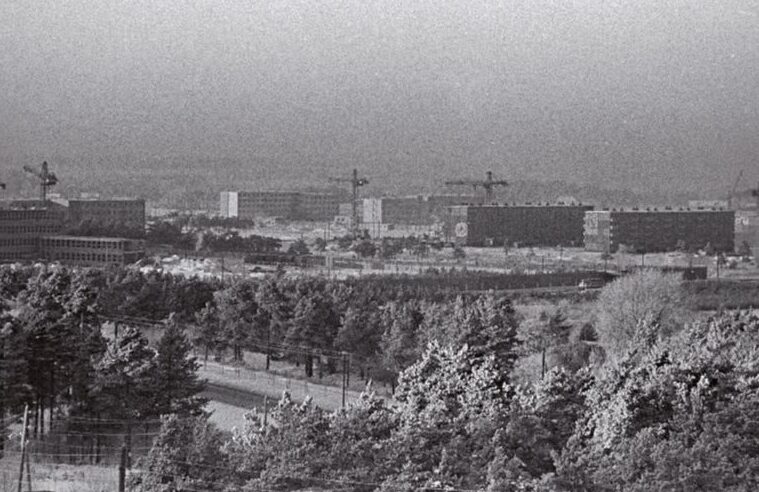

Stseenid linnaelust (Autumn Ball: Scenes from City Life), published in 1979 in Soviet Estonia by a writer hailed early on as a ‘prodigy of Estonian literature’, whose life was cut short at just sixty-one years of age. With striking precision, Unt describes life in Tallinn’s Mustamäe district – an urban microcosm that rivalled the Western urban jungle in its social discord, psychological isolation and atmospheric density. Once a symbol of progress, Mustamäe has lost its shine – much like countless other socialist-era housing estates from Berlin to Budapest, from Prague to Gdańsk.

In this microcosm, we encounter six main characters whose lives intersect superficially, yet deeper connections remain fleeting. They are the poet Eero, the architect Maurer, the doorman Theo, the hairdresser August Kask, the telephone operator Laura and young Peeter. Each of them represents the contradictions of modern existence, entangled in the social and psychological upheavals of a system that seemingly seeks to regulate everything but leaves people alienated. In essence, Autumn Ball is a collective novel, a web of solitary lives woven into a single, fragmented urban narrative.

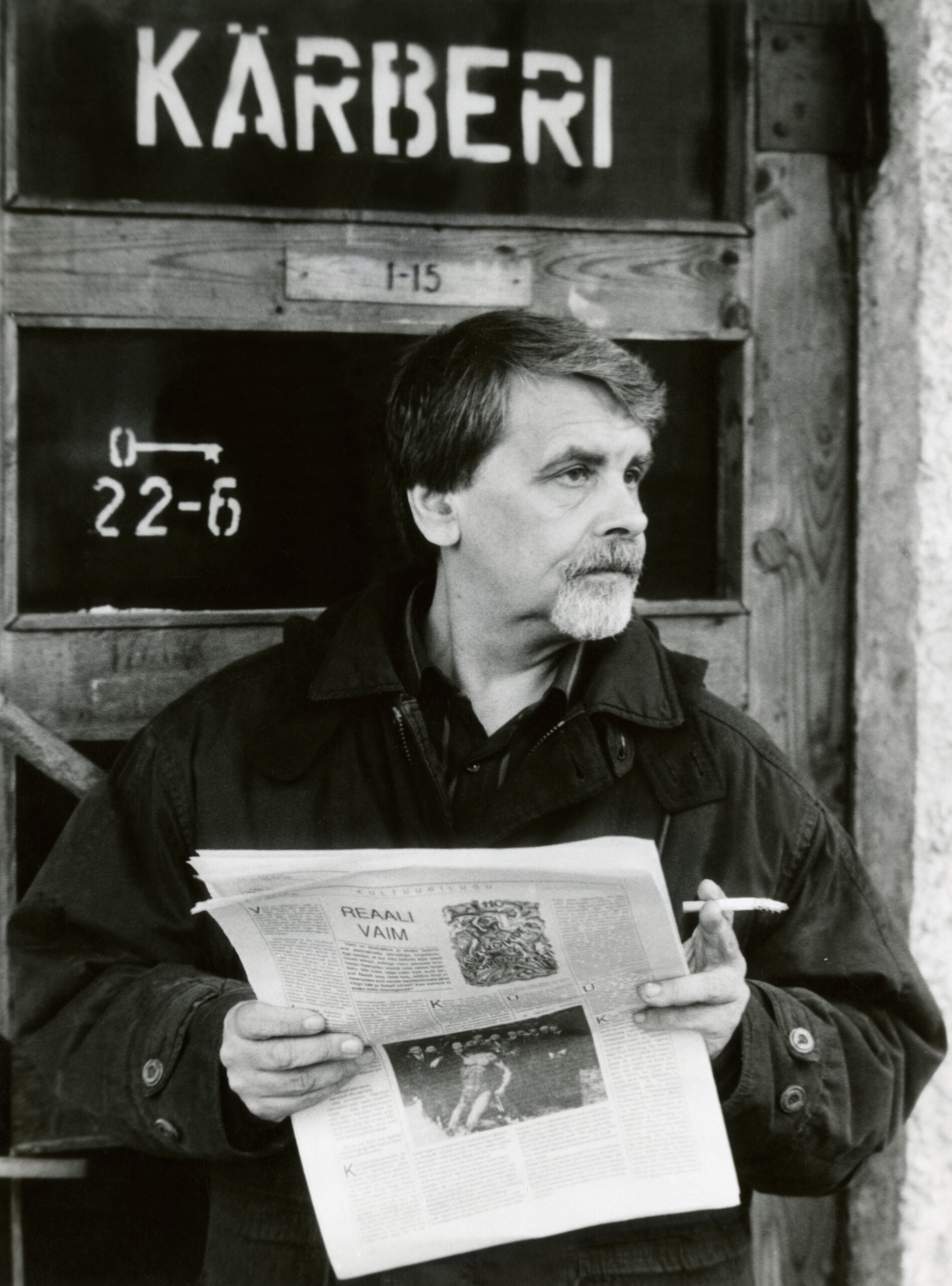

Mati Unt, who was in his early thirties when he wrote the novel and lived in Mustamäe himself, knew that a cold, constructed living space is not conducive to life. This perspective is reinforced with quotes from French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, whose Poetics of Space is just one of many references that Unt, who introduced postmodernism into Estonian literature and theatre, draws upon. Unt does not describe an exclusively Soviet or socialist phenomenon; references to the system in which the work was created are well measured and subtle – for example, wine from Georgia, militia on the streets checking people’s IDs, official statistics from the USSR.

There is no Homo sovieticus in Unt’s writing. Rather, it is modern humans, female and male, young and old, from different backgrounds, all relatable and quirky in their own ways, who get a voice. The emotional weight of the characters’ environment is ever present, and as they move through their lives tensions sometimes boil over into eruptions of violence, often fuelled by alcohol. The only one who seems truly enthusiastic about the new form of housing is, ironically, architect Maurer, who himself has made a modest contribution to the creation of Mustamäe.

It is surprising that Autumn Ball, despite its satirical take on the seemingly progressive yet often bleak and ennui-filled way of life in the Soviet Union, as well as its innovative approach and international feel, did not fall victim to censorship. Even more remarkably, the book was initially printed in an edition of 28,000 copies, which sold out within ten days. Since then, there have been numerous reprints and new editions, with the latest published in 2025 by the renowned publisher Tänapäev.

One reason for Unt’s success, and for the success of Autumn Ball in particular, may lie in his deep understanding of the contrasts in Estonian society, drawn from his own experience. He was a city dweller through and through, but he came from a remote place, where he lacked intellectual and artistic support structures. Yet he was considered the most modern, the most cosmopolitan author of his time, according to fellow writer Mihkel Mutt, who published a comprehensive biography of Unt in 2024 titled Liblikas, kes lendas liiga lähedale. Mati Unt ja tema aeg (The Butterfly Who Flew Too Close: Mati Unt and His Era) – a year that saw a veritable Mati Unt boom in Estonia.

Although the lives of Unt’s six protagonists unfold in Mustamäe, amid panel blocks of flats between five and nine storeys high, their thoughts drift far and wide, to other continents and even distant planets. Theo, who works as a doorman at a local restaurant and meticulously records his affairs, has a penchant for astronomy and metaphysical musings. Then there’s the barber August Kask, who casually remarks how the length of men’s hair in magazines from the West seems to fluctuate – a subtle nod to the cultural shifts of the ’68 movement. Yet another character, Laura, escapes her routine as a worker and single mother by immersing herself in a TV soap opera, which shifts between settings in Britain and Bavaria.

The film adaptation of Autumn Ball was released in cinemas in 2007, two years after Mati Unt’s death. It loosely follows the source material (the actors were not allowed to read the book during preparation for the filming) and affords itself a certain freedom – as, for example, when the author’s alter ego, Eero, is renamed Mati on screen. The film, which has become a much-referenced cult classic, received an award at the Venice Film Festival and has frequently been compared to the works of Aki Kaurismäki. Certain similarities to the Finnish filmmaker can also be found in the book, although the novel was published prior to his debut as a director in 1983. In fact, it is not entirely unlikely that Kaurismäki had read the book, which was published in Finland by Gummerus in autumn 1980 and received a considerable amount of positive feedback.

The book has been translated into more than ten languages – there is even an English version, published by the Estonian publisher Perioodika, which probably did not receive an awful lot of recognition in English-speaking countries. The German translation was published two years before the fall of the Berlin Wall by Aufbau, the largest publisher in East Germany. Not unusually for the time, the book was translated via Russian, resulting in a convoluted, overly complex style that bears little resemblance to the original. This calls for a new German translation, as it is precisely Unt’s laconic voice that lends the novel its wit and lightness of touch. Unt does not evaluate; he describes modern life in all its absurdity, and in doing so is ‘radically empathetic’, as Estonian art historian and playwright Eero Epner writes in his afterword to the 2025 reissue of Autumn Ball. Yet Unt’s writing is not only empathetic but also associative, nervous and erratic – he frequently leaves the narrative, zooms out of the action, until the protagonists are no longer in sight, weaving in encyclopaedic, incidental and anecdotal elements, only to return to the story as if nothing had happened.

The absurdity of the city is only surpassed by the even greater absurdity of the countryside. At the opening of the book, a freight train rolls through the countryside, unmanned, and a famous opera singer goes missing. The fact that the novel does not begin with ‘Scenes from City Life’, as the subtitle suggests, but with two anecdotes in rural settings, is no coincidence. The journey from the countryside to the city is a central motif in Estonian literature and a metaphor for the development of Estonian society, particularly in the works of the great Estonian literary classic Anton Hansen Tammsaare (Truth and Justice) and his literary successor Karl Ristikivi (Tallinn Trilogy). Mati Unt, who greatly admired Tammsaare and successfully staged his works in Estonia’s major theatres, stated in an interview that Autumn Ball is precisely a book about the shock experienced by the people of Estonia when they were forced to urbanize at breakneck speed, ultimately leading to widespread alienation.

In Unt’s world, a person’s drive to shape their environment extends even to nature itself: strange pipes rise from the ground, kitschy castles stand abandoned amid the landscape and mysterious railings lead from the depths of the forest straight into the sea. Yet in Autumn Ball, nature does not merely serve as a backdrop, it acts as a unifying element – through nature, the characters silently connect with one another. Natural phenomena, such as an approaching thunderstorm or the first snow, blur the individual episodes and reflect the inner state of the protagonists.

This inner state, imbued with wonder and a kind of innocent curiosity, is no coincidence either. Mati Unt himself was an author of great enthusiasm, often described as hot-headed – a temperamental intellectual who viewed the world with an almost naïve gaze. This attitude finds its counterpart in the character of the boy Peeter, who watches the thunderstorm over the city with a mixture of awe and fascination. In Peeter, several facets of Unt’s literary temperament come together: the melancholy, the fine humour and a gravity that is sharpened by childlike directness. When he randomly calls people and asks them seemingly trivial riddles, they are, in truth, existential questions – simple, honest and genuine.

In such moments, not only is the unique sound of the novel tangible but also its sense of temporality. That Peeter uses a traditional telephone to make calls now carries a certain nostalgic charm, yet this detail points to a deeper difference: life had a different rhythm back then. People had time, space for silence, for boredom – a state that, for Unt, does not signify a lack but opens up possibilities. Today’s constant accessibility and perpetual flood of information thus leads to the emergence of new forms of isolation.

A charming counterpoint to the loneliness of the characters is the great humour in Autumn Ball. One example is a scene in which Eero, slightly drunk, ends up at a party with people he has just met. He agrees to fetch more alcohol, but after an odyssey through the identical buildings of Mustamäe he finds himself, confused, in Laura’s apartment. Without a word, he sits down beside her on the sofa and watches television with her.

The novel culminates in a tragic accident, but what has fatal consequences for some brings happiness to others. One might almost call it a happy ending were it not for the fact that Unt doesn’t let his protagonists off the hook. Autumn Ball is Mati Unt’s most important work – an outstanding book about modern life that feels more relevant today than ever. While Döblin’s Berlin and Dos Passos’s New York have long found their place in the canon, Unt’s Tallinn is a literary space that today deserves to be rediscovered as an Eastern European variant of the modern urban novel, both prescient and compelling.

Maximilian Murmann

EXCERPT FROM THE NOVEL

Read an excerpt from Mati Unt’s The Autumn Ball, published in EstLit (Spring 2025).

Maximilian Murmann

Maximilian Murmann (b. 1987) is a German translator of Estonian, Finnish and Anglo-American literature.